Bulgaria — embracing tradition with an eye on the future

by Judith Rosen, Alexandria, VA

Having completed a tour of Romania, Judith Rosen continues her month-long trip with a visit to Bulgaria.

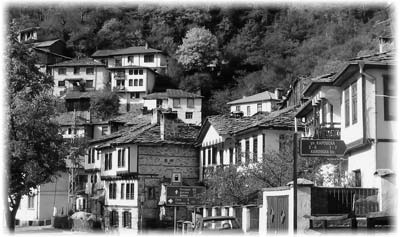

Veliko Turnovo

Following our visit to the Thracian tomb at Sveshtari, it was another 160 kilometers through varied countryside to Veliko Turnovo, where we were warmly greeted by the owner of the Gyurko Hotel. Small and cozy and overlooking a hillside panorama, here we would spend three nights.

Our room was posted at $75 a night and included free laundry and Internet. Its snug restaurant was considered one of the best in town, but we also tried the elegant Astra, which was excellent as well.

After a quick visit to the Sunday market, seeing leeks four feet long and radishes the size of softballs, we strolled the tidy main street lined with many souvenir stalls. Exploring the steep alleys, barely cobbled or entirely dirt, however, revealed tiny, crowded houses in poor repair where, in places, laundry and cooking were being done outside.

Climbing Tzarevets Hill, past reconstructed walls, foundations and the palace, I reached the church at the top for a 360-degree view.

Arbanassi and Shipka Pass

We then drove to Arbanassi and its 13th-century Holy Virgin Monastery, where we were greeted by five elderly nuns and invited to visit their private quarters. Bulgaria today is said to have only about 110 monks and 80 nuns, mostly elderly, unlike those we saw in Romania. This means that many of the revered religious sites have no residents.

Arbanassi is one of many Bulgarian “museum villages,” which are required to be preserved without exterior changes. However, beside the terrace of the restaurant where we had lunch, a huge water slide loomed from the swimming pool below.

Monday we headed south about 45 kilometers, vying with trucks on the main north-south mountain road, to Shipka Pass at about 6,000 feet.

The national monument here commemorates the Russian victory over the Turks which ended Ottoman domination of the area, an important turning point in Bulgarian history.

The tower/museum is supposed to be reached via a 200-step stairway, but, seeing no guards, we drove up. Against a blast of icy wind, I made it to the 7-story tower, each floor containing an exhibit of drawings, lithographs or paintings depicting the horrors of this battle in which thousands of Turks and Russians were killed or froze or starved to death on those steep, snowy slopes.

As I climbed to the upper floors, the sound of howling wind grew louder until, by the time I reached the final winding flight, I wasn’t sure I wanted to open the narrow door to the balcony. But I did and, holding tight to the railings, was rewarded with spectacular views in all directions.

Returning through Gabrovo, we could see the devastating effects of the collapse of the Communist economy. There were huge empty factories and decaying buildings. In the drab town center is the House of Humor and Satire, which unfortunately was closed Mondays. In the National Museum of Education, with its model of an 18th-century classroom, we heard about the disciplinary tactics and learning routines employed in past centuries.

Tryavna and Shoumen

Our next destination, Tryavna, is a center of woodworking, icon painting and textiles. These trades, together with growing tourism, have enabled this town to prosper, with neatly whitewashed buildings, souvenir shops, eateries and other businesses.

After visiting the woodworking museum, we stopped on the main square for tea and tzaravul, a local pizza-like pastry shaped like an old-style Bulgarian peasant shoe.

From Veliko Turnovo we headed east to Shoumen, stopping at one of Bulgaria’s oldest mosques. Then we wound our way up the steep hill to a stunning monument dedicated to the creators of the Bulgarian state. The area was deserted — we were told almost no one goes there — so we drove rather than walked the long pathway. We could hardly stand against the fierce wind, but the sculpture was magnificent as was the view over the town and countryside.

Varna

We continued on to Devnya, where a museum had been built over an excavated fourth-century Roman villa, preserving some of the mosaics.

Eastern Bulgaria is a trove of ancient sites, with more being unearthed yearly.

Approaching Varna, we stopped at Pobiti Kamani, an extensive area of natural stone columns and other formations whose origin is still being debated.

After checking in at the dreary Aqua Hotel, located on a noisy street where our windows overlooked freight yards and the train and bus stations, I explored nearby unpaved streets and winding residential areas, finding an early period building now used as a wedding center. These centers are much in demand by Bulgarians, now no longer required to be married only in state offices.

Eventually I reached a shopping street, a curious mixture of boutiques, secondhand clothing stores and auto parts shops, that was chained off at the end. I had reached the city center, a broad pedestrian area of fountains, cafés and shops, the main street of town.

At the edge of the area was a lovely ethnographic museum, which we found again the next day only with great difficulty.

Seaside resorts

• Wear your sturdiest shoes.

• Finding Western-style toilets can be a problem in rural areas, even at restaurants. Newly constructed gas stations are your best bet. Always carry toilet paper.

• Sausage and cheeses were used extensively in cooking, and most food was very salty.

• The type of small hotels and inns we requested usually involved steep stairways.

• Never change money on the street. Bankomats (ATMs) are plentiful.

• Many places accept euros.

• Our guides kept saying they were not allowed to alter anything on the itinerary until I insisted it was my tour, not the company’s. If you use a tourist agency, make sure you have an understanding about this.

• Do as much research as possible on your own before you go. No guide can know everything.

During the next two days, even though we knew most of the Black Sea resorts would be closed for the season, we visited four different areas. Starting at Golden Sands, Bulgaria’s best-known resort, we were amazed at the burst of new, glitzy highrise hotels nudging the shore, the first significant construction we had seen in the country.

The beach and broad plazas were deserted on this blustery day, but we were assured that, in spite of the breakneck construction of new hotels, it would be hard to find a room in summer as the area would be inundated by tourists from Western Europe and Russia.

Heading south, we came to Bulgaria’s first seaside resort, Saint Constantine and Helen, begun in the 1960s as reparation to Czechoslovakia and now occupied by stately, all-inclusive resorts on extensive, park-like grounds. The area is booked two years in advance by Germans and Russians.

South of Varna and several other small beach enclaves was Sandy Beach, the most family-friendly resort complex, with mostly smaller hotels and apartments, several huge water parks and a long concourse behind its dunes, protected from the wind. Here, again, a building frenzy was evident. Irena told us she hadn’t been able to find any accommodation there during the summer of 2003.

We spent that night at Hotel Mistral near the bridge to the island of Nessebur, another preserved site. There is evidence of settlement on this strategically placed island dating back to the fourth century B.C. About 40 churches, most in ruins, now occupy this tiny area.

The island was supposed to be closed to vehicles, but as no one was enforcing this, Lozan, our new driver, forced the car through the tight alleyways lined with closed eateries and shops. Suddenly, about 10:30, shutters clanged open, covers were whisked from stalls, and shelves of merchandise burst onto the streets. As we neared the town gate we saw why: busloads of tourists were arriving outside the gate.

In shops I was routinely greeted in German, the only language we heard in the area.

On our way back through Varna we stopped for lunch, over my objections, at the Happy Bar & Grill, an American-owned fast-food chain restaurant where, to my surprise, we found great salads and other dishes explained on a picture menu in English. These restaurants are popular among Bulgarians, offering good food within their budget.

Sozopol

Finding a place for lunch along the coast to the south the next day proved almost impossible, most eateries being shuttered for the winter. Seeing a place open in Sozopol, we darted in eagerly to find an elegant restaurant called Cote d’Azur overlooking the harbor. After complimentary appetizers, we had a number of different menu items plus brandy, resulting in tabs of about $10. When I asked for a brochure, they said they had none because they didn’t need any publicity.

We were the only guests at Sozopol’s unheated Amon Ra hotel, which had a beautiful view of the angry sea lashing against the rocks below. The owner just gave us the key and went home, forgetting to turn on the hot water!

In the morning, we found an English couple had arrived during the night. They were looking for a place to buy, along with what they said was a virtual “gold rush” of their countrymen, snapping up properties in the smaller developments around Sozopol at a fraction of what they would have to pay at home.

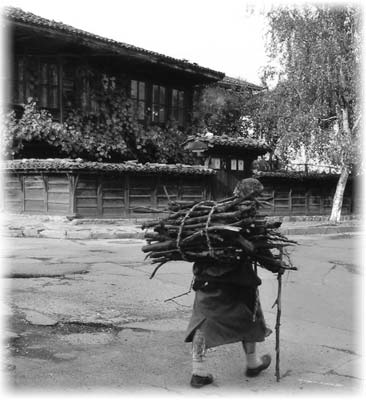

Kotel

Heading inland again, we passed extensive walnut and almond groves and vast vineyards where harvesting was in process. Nestled in a pass among the steep, autumn-tinged hills was Kotel, already a strategic settlement in Thracian times and for centuries receiving preferential treatment in exchange for guarding the pass. Today it is home to one of only two folk music and dance schools in Bulgaria, as well as being a furniture- and carpet-making center.

Irena had been told it was not possible to visit the carpet workshops, but we went and were enthusiastically received. We also visited the tastefully arranged natural history museum, the first in the country outside Sofia.

Into the mountains

The village of Jeravna is considered the best-preserved old-style town in Bulgaria, with buildings only in the earliest Revival style.

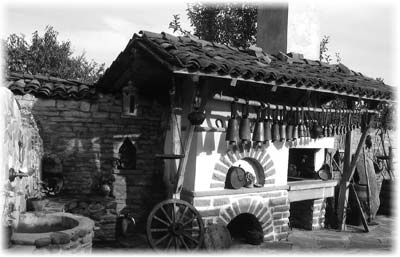

Finding our way to the Vaselin Vasilev pension was a challenge. Unmarked roads, hills far too steep for cars, and walls we could barely squeeze between made for an exciting ride. The reward was a totally charming inn artfully decorated with antiques and built around a courtyard displaying farm tools, huge copper cauldrons and rows of cowbells, each with a different tone.

The stone-walled dining room was decorated with hunting paraphernalia, a fire was crackling in the hearth, and the local chicken specialty arrived topped with a sputtering sparkler. At breakfast we had our first menu variation in three weeks: two types of doughnut-like pastries typical of the area.

The mountain drive on the way to Kazanluk gave way to fields of lavender, roses and peach orchards. After driving deeper into the mountains, we arrived at Koprivshtitsa. This was also a preserved town, but it contained examples from three architectural periods.

The Dalminets family hotel, where we spent that night, was spare but well heated. The recently opened Panorama Hotel, which we visited, overlooked the town and was the most modern hotel we saw there.

Plovdiv

We arrived in Plovdiv for two nights at the Hebros Hotel, a 6-room Renaissance house in the oldest part of town. Each room and the two reception rooms were individually furnished with antiques. It offered 4-star comfort, with a fitness center, sauna and an excellent restaurant. Our 2-room suite was listed at $145 per night.

After threading our way through Plovdiv’s steep cobbled streets, we had coffee overlooking the remains of a Roman amphitheater now used for opera or other performances.

At the foot of Old Plovdiv, next to a 14th-century mosque, is a colorful artists’ mart and the beginning of a long pedestrian mall which ends at a huge shaded park. Restaurants and cafés were bustling, largely with young people, and shops displayed trendy merchandise.

On the way out of Plovdiv, we stopped at a vast market where, Irena told us, prices were about half of what they would be in Sofia. There we sampled mekitsa, a delicious, airy form of doughnut, piping hot.

Local specialties and spectacular scenery

Heading south toward the Rhodopean Mountains, we visited the Bansko Monastery, begun in the 13th century. The chapel and the 16th-century kitchen and dining hall with well-preserved frescoes can be visited.

Stopping at the pleasant streamside Rhodopean Inn for lunch, we found some local specialties on the menu, including several varieties of polenta pies with meat, spinach, cheese or other fillings.

Then we continued toward our destination, Hotel Kalina in the whitewashed and very vertical town of Shiroka Luka, near the Greek border. When we arrived, it was closed — they had forgotten we were coming. After the owner had been located and we settled in, I labored up steep city streets, some of them actually steps. Many of the tiny houses clinging there had chickens and rabbits caged underneath.

The all-day drive the next day through the mountains and Trigrad Gorge was sensational. Beyond Dospat, the scenery changed abruptly to rolling hills with terraced fields. When we stopped we could hear tinkling bells from grazing cows in all directions.

Following small side roads, we visited some isolated villages in an area originally planned for resettlement of dislodged Bulgarians but now being bought eagerly by foreign investors.

Vineyards stretched in all directions as we neared Melnik, a wine and tourist center where every inch of the narrow valley was being converted to new hotels. It was 72 steps up to the entrance of the St. Nicola Hotel, where we spent the night.

On to Rila

Leaving Melnik, we snaked around the bases of distinctive sandstone columns, known as The Pyramids, each with a crowning clump of greenery, on our way to a 13th-century Roman monastery.

Continuing north through deep gorges, we stopped at a cluster of restaurants, finding a table overlooking the Strouma River spanned by a swaying footbridge. Then it was on to Bansko, Bulgaria’s largest ski resort, where an avalanche of visitors is causing another construction boom. The small “Old Town” there is a restoration.

The Durchova Kushta Hotel, where we stayed, had a dining room, but we went for dinner at the newly reopened and very lively 1792 Molenita, where the chef/owner created a mountain of food for us.

Approaching Blagoevgrad, we saw a wall of apartment blocks rising abruptly from the flat plains that typified the outskirts of both Bulgarian and Romanian industrial towns. From there it was a short ride to the Rila monastery, where busloads of schoolchildren were being shepherded by their teachers to appreciate this stunning building and its magnificent chapel.

On the way back to the town of Rila, we stopped for a trout lunch, a specialty of the Jabokrek restaurant located next to a rushing stream. Finally reaching Sofia, we settled for three nights at the comfortable but overrated Arts Hotel; the nightly rate was posted as $175.

Sofia

Saturday, after touring Sofia’s Ethnographic Museum with its extensive collection of national dress, we toured the main part of the city. Surrounded by the Sheraton Hotel and several ministry buildings were the remains of a second-century Roman street and homes and a fourth-century church.

We also drove to Boyana to see its 13th-century frescoes, unusual because of their deviation from strictly prescribed church themes of that period and notable for the excellence of their illustrations unmatched for many centuries.

Sunday morning proved an ideal time for sightseeing in downtown Sofia. Unlike during the rest of the week, the streets were calm and clear. Sunday service had already begun when we reached the cathedral. We stood for about an hour (there are no seats in Orthodox churches) watching brilliantly robed priests and listening to their melodious prayers alternating with the superb choir.

Outside the cathedral was the Sunday flea market. Items offered included microscopes, Soviet army hats, jewelry, antique samovars, watches, handicrafts, jams, etc. The stalls stretched all the way to the beautiful Russian church.

By the time we finished lunch, traffic had returned to its usual frenetic conditions, so we did the rest of the day on foot. Many side streets were obstacle courses of dumpsters, with sidewalks cluttered with parked cars and torn-up pavement. But the main thoroughfares were crowded and, contrary to our guidebook information, most shops were open.

One night we ate at the widely advertised and recommended Beyond the Alley Behind the Cupboard (31 Budapest Str.; www.beyond-the-alley.com) — pleasant and good. Our bill there was $50, beyond the reach of most Bulgarians; only American and British tourists were there.

Another night, on a decrepit street, we found Monastirska Magernitsa (67 Khan Aspuruh), featuring unusual “forgotten” Bulgarian dishes from recipes obtained from monasteries and families in different regions. Their 36-page menu had humorous touches, and the portions were huge, the service was outstanding and the food, delicious. The décor was charming, and folk artists in national dress performed. Our bill was about $28.

The following day we flew to London for an overnight stay on our way home. Including everything except lunches and dinners, the price for our 29-day trip with Alexander Tour Company (Sofia, Bulgaria; phone/fax +359 2 983 33 22 or visit www.alexandertour.com) was $3,911 per person. Romania had cost $1,614 per person for 12 days and Bulgaria, $2,297 per person for 17 days.