Searching for answers to the mysteries of Bolivia’s Tiwanaku

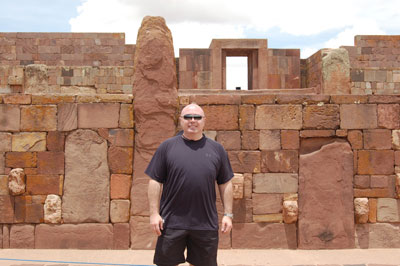

by Jeff Houle, McLean, VA I was in Tiwanaku in western Bolivia, 44 miles west of La Paz and close to the border with Peru, when I began to understand why some people would think that aliens constructed the ancient walls found there. Not even my site brochure would fit into the mortarless joints that separated the monstrous monoliths, whose journey to this place is not easily explained.

The site

The pre-Columbian site of Tiwanaku sits 13,000 feet above sea level in the dry Andes Mountains. Occupied between AD 500 and 950, the city was inhabited, at its peak, by up to 30,000 people before a drought pushed the population out of the region. The residents of what would have been an imposing city left no written record of their story, leaving the majority of their history to the conjecture of modern archaeologists and science fiction enthusiasts.

Although there are other ancient sites in the area, such as Lukurmata, once a ceremonial center, Tiwanaku, itself, was the most important, serving as the religious and administrative capital of a vast empire that predated the famed Incas. All that now remains for travelers to visit are the walls and foundations of a few buildings, as well as a few standing gateways, on a patch of land that occupies only a small fraction of the original 2.6-square-mile expanse. The most important of these structures, arguably, is the cracked Gateway of the Sun, which has become something of an icon in Bolivia. This stone arch is inscribed with images of “staffed gods,” anthropomorphic figures bearing staffs, most likely ritual practitioners, according to archaeologists. Although much of the city has not stood strong against the test of time, what still exists, and what is known of what used to exist, is more than enough to stir up questions about the mystery of the place.

Raising questions

Staring up at walls that dwarfed my 5'10" frame, my first question was, ‘How did these enormous red sandstone blocks, each weighing up to 130 tons, get to Tiwanaku, 10 kilometers from the nearest quarry?’

It is also difficult to explain how a culture without 18-wheelers could manage the transport of the 40-ton green stones (andesite) that were used for the site’s intricate decorative carvings. They were brought to Tiwanaku from the other side of Lake Titicaca, a distance of 90 kilometers over water and another 10 over land. Pointing to the remains of what appeared to be ancient canals, my Bolivian tour guide explained the popular theory, which says the blocks were transported by reed rafts on rivers and canals to Tiwanaku after being hauled on logs from their original sites. Small pools of water rest in these canals now, showing that they were once capable of holding liquid, but imagining them as the great tools of movement that they were said to have been required a stretch of my imagination. Assuming that my tour guide was correct and that transporting the stones was indeed possible, the mysteries of Tiwanaku are still far from solved. Once the giant stones arrived, how did the buildings’ architects figure out a way to stack the blocks with such perfect precision? No mortar was used — nor was it needed, as the joints seemed perfectly crafted, even to my modern eye.

Out of this world

A creative few have clung to the imaginative theory that such achievements could have been accomplished only by technical advancements not known to mankind at the time. These theorists say the precision of the joints and the magnitude of the structure must have been the result of aliens and their extraterrestrial techniques.

Even the Incas, who discovered Tiwanaku hundreds of years after it had been abandoned, had their own theories to relieve their discomfort with the idea that an advanced culture could have existed before their own. They claimed that the first Incas were created from stone by the deity Viracocha and that the monoliths stand as a solemn reminder of that act. I remain skeptical of these more extreme theories, though I admit it is easier to explain the mysteries with tales of visitors from space than to imagine all of the blood, sweat, tears and probably lives that must have gone into the construction of this amazing city. Places like Tiwanaku remind travelers of the incredible work mankind is capable of. This is one of the reasons people travel, after all: to see, up close, what remains of this world’s history so that we might better know how we got to where we are and to gain insight into where we might be going. I left Tiwanaku still pondering my questions but also feeling uniquely privileged to have experienced what remains of such a remarkable period of human history.

The details

I traveled to Tiwanaku in November ’09 and used a local guide named Rene Jaldin Andrade, who was based in La Paz. He was very good. Though his English was less than perfect, he tried really hard. The cost for his services was about $70 for the day.

If you decide to hire a local guide on your own rather than through a travel agency, it’s always good to make sure he or she is certified by Asoguiatur, the local association of tour guides. Most visitors to this area come for the day from La Paz. For the cheapest travel option, catch a bus outside of La Paz’s main cemetery. The trip takes between one and 1½ hours and costs less than $2. You can also catch a ride with a tour bus service for about $1.50. Try Transportes Tiwanaku (phone 7191 4889). Another option is to hire a taxi from La Paz to take you on the round-trip journey. Including wait time, this should cost about $30 to $40, and most hotels can help you find a safe driver. The last option, and perhaps the most popular, is to arrange a tour with a bilingual guide from a travel agency in La Paz. Most travel agencies will offer half-day or full-day tours. I used Transporte Turistico Bolivia (phone 591 2 231 6971). Entry to the main site costs $10, and it’s open from 9:30 a.m. to 4 p.m. Entry to the on-site museum, Museo Litico Monumental, also costs $10, and it is open 9 to 5. If you would like to stay the night in the area, there is a small village next to the site. I stayed there at the Gran Hotel Tiwanaku (Bolivar 903; phone 289 8548), the nicest hotel in town. At $30 to $40 per person per night, it was also a good deal.