A West African journey continues with sites in Burkina Faso and Ghana

Jim Sill and his travel companion Jenna continue their January-February ’07 overland journey through West Africa, embarking a bus in Burkina Faso for Bobo-Dioulasso.

When we reached the bus station in Mopti, the big buses were leaving, one by one.

“Which one is ours?” asked Jenna. “Maybe we can get on board early.”

I asked the ticket agent. He pointed to a beat-up minibus that we hadn’t really noticed. As he pointed it out, the driver opened the door and it came off in his hand — not a good sign.

The bus was supposed to leave at 5 p.m., but it didn’t because they were waiting to fill that puppy. When they started to pile luggage on top and the number of people who intended to ride it became apparent, Jenna looked at me with sheer dread: “They can’t get all these people in there, can they?”

So began the ugliest ride of my life. Because we had made early reservations, we got to sit behind the driver (where a head-on collision would have been fatal). Jenna was wedged next to a window that didn’t open and I was in the middle, seated next to a big man who sat next to a woman on the other side, our shoulders at 45-degree angles because there wasn’t enough room to sit shoulder to shoulder.

About two hours in, a grinding sound came from the gear box.

“What’s that?” asked Jenna.

“That’s the sound gears make before they spill out all over the road,” I opined.

About five minutes later we heard a loud snap followed by metal scraping on asphalt. The bus pulled to the side of the road. I grabbed a small flashlight, got out with the rest of the passengers and walked back up the road. There, in the middle of the road, was the drive shaft.

The bus’ mechanic climbed onto the top of the bus, retrieved some twine he had used to secure the baggage and crawled under the bus with the drive shaft and a few tools.

I soon became a believer in small miracles and grubby mechanics. In about two hours we were on our way again.

There were many more breakdowns, stretches of really bad dirt road and agonizingly long stops. The bus driver seemed to know a lot of people and stopped to chat with every one of them.

We pulled into Bobo late in the afternoon the following day, 21 hours after the trip from hell had begun. Jenna climbed down from the bus stiffly, hoisted her rucksack onto her back and promptly fell over into the dirt from numbness in her legs.

Bobo-Dioulasso

We moved into the centrally located Hotel Teria (Av Alwata Diawara; phone 20 97 19 72), where, for about $20, we got a room with no hot water but a good bed and mosquito net.

The next day we explored Bobo, an arty place with lots of shops selling African artifacts, plus a couple of discos featuring Burkina Faso musicians. There appeared to be no other tourists in town, so we were “it.” We attracted hustlers everywhere we went.

That night we had drinks at Les Bambous, a French-owned cabaret featuring local musicians and beautiful patrons from all over Burkina. It consisted of a large, walled-in patio with a gilded bar, a sound stage, lots of tables set in low light around a massive cluster of bamboo and a well-

illumined display of original fine art on the far side. The beer was cold, the entertainment, hot.

The next day I went to a bank to get a cash advance with my Visa card. “No,” they said; I needed a pin to go with that Visa. “Must be an aberration,” I thought, but by the time I got the third refusal for the same reason I knew I was in trouble.

I implemented Plan B: with enough money to go to Banfora, our next stop in southwestern Burkina, and make it to Ouagadougou, Burkina’s capital, I figured I could use the Visa to pay for hotels, and we could get money wired to us via Western Union when we got to Ghana.

Now we needed a guide for Banfora. We never had any problem meeting people when we sat on the streetside patio of Bobo’s local patisserie. So we went there, sipped our coffee and waited to see who would turn up.

Waiting for Moussa

At first, the usual “guides” showed up. I guess they sensed we were finally at a point where we would actually hire somebody.

Finally, in an impromptu game of musical chairs sans music, a vacant chair became available and off the street strode a man with a side bag and some documents. As we would soon learn, this was Moussa.

Moussa’s English was pretty good, and he had a presentation booklet consisting of photos of him with foreign tourists in the places we wanted to visit. Not only that, he had a French travel magazine which featured him prominently as a guide extraordinaire.

He laid out his fees and promised to meet us that evening to firm up our travel plans for the next day.

That evening I called Moussa on his cell. We were to rendezvous at the patisserie in 15 minutes. We went there and waited. And waited. But no Moussa. I went back to the hotel, puzzled. He had seemed so reliable.

Back at the hotel, a hustler told us that Moussa had waited there for us for a few minutes, then left. I went back to the communications center, called Moussa and he confirmed it.

“I thought we were going to meet at the patisserie,” I said.

“I thought you said your hotel,” he replied.

“Okay,” I said. “I’ll meet you at the hotel in five minutes. THE HOTEL.”

We went to the hotel and waited. And waited. No Moussa.

I was fed up. “We’ll go on our own tomorrow,” I said to Jenna. “We’ll hire a local guide when we get to Banfora.”

The next morning I went to get bus tickets. Moussa was waiting for us at the ticket counter.

“I waited for you at the patisserie, but you never came,” he said.

Before I could say anything, he told me he already had our tickets and invited us for a cup of coffee before the bus left. I let it go.

When we arrived in Banfora, Moussa had a car waiting for us. We bought a picnic lunch and proceeded to Les dômes de Fabédougou, unique rock formations estimated to be 1.8 billion years old. The only other similar formations, called the Bungle Bungles in Australia, attract thousands of visitors annually. But on this day we had the domes to ourselves, free to hike where we wanted.

After wandering the domes, we drove to nearby Karfiguela Falls, beautiful waterfalls reached by hiking through an old mango orchard. Above the main falls are smaller falls with pools perfect for swimming.

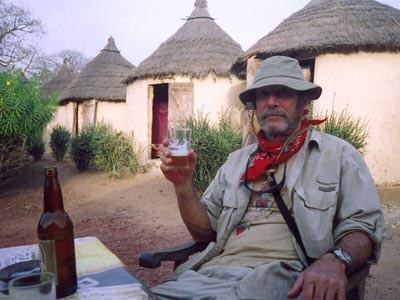

We spent the night at Campement Kegnigohi (phone 76 42 6902 or 70 24 68 93), a small village with individual sleeping huts, furnished with lumpy, less-than-clean beds and mosquito nets, on the edge of a hippo lake. It was there that I came to understand why we miscommunicated so often with Moussa. Moussa was a stoner. He told us he was a “rasta mon” but that he kept his hair short so he would be more appealing to travelers.

The next morning we got a pirogue (local canoe) to take us across the lake to where hippos were hanging out. Then it was back to Bobo in time to catch the bus to Ouagadougou. In Ouagadougou we found a hotel that would take Visa.

Show me the money

By afternoon the next day we were in Tamale, Ghana’s northern transportation hub — not much of a place for travelers except for those wanting to sample the fufu in the G Restaurant across from the STC bus station. Of Ghana’s two staple foods, fufu and kenkey, I preferred the former; I fufu’d every chance I got, but I only kenkey’d once, which was enough.

Fufu is a glob of unsweetened manioc dough which sits at the bottom of a bowl of spicy soup served with a chunk of goat, chicken or guinea fowl and eaten with the fingers. Kenkey is a blob of fermented (i.e., sour) maize or millet dough wrapped in leaves and served with a blistering-hot sauce, sometimes with beans, also eaten with the fingers.

We stayed at the Picorna Hotel (phone 071 22070/672, picorna hotelgh@yahoo.com). Although we asked for an average room, they gave us the Executive Suite II, the most expensive room they had. They had also recently doubled their rates over what the Bradt guide had indicated; additionally, Ghana has added to all hotel bills a VAT of 12%-18%, depending on who’s counting, bringing our bill to $47 a night. Relative to where we were, this was grossly overpriced, but we had to stay here because of my money situation.

The next morning found me on Western Union’s doorstep waiting for them to open. I was greeted by smiles and piles of money, and I do mean piles. One thousand dollars fetched over nine million cedis.

“Here, sir,” said the teller, handing me a shopping bag. “You’ll need this.”

I shoved the money down my pants and waddled to the bus station for tickets to Mole National Park, Ghana’s premier game reserve.

Although Mole is not that far from Tamale, the dirt road added some serious hours to the journey. Our Bradt guide said that Mole is overlooked by most travelers, but there were no vacancies when we arrived. Jenna and I had to settle for a dorm room, which we shared with two Dutch girls.

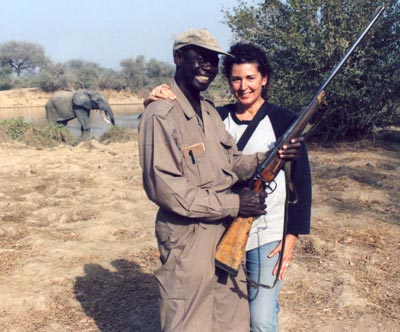

We went on safari the next morning, hiking through heavily wooded savannah with an armed guide. We saw a wide variety of animals, ranging from elephants to warthogs. After a 2-hour hike, we retired to the pool overlooking one of the park’s large water holes that attracted elephants, baboons, bushbuks and other animals throughout the day. We swam, drank cold beers and watched the animals, some of which approached poolside.

We were able to upgrade to a large private room, with fan and bathroom, for about $25 per night. We stayed for a second day.

Ghana’s Gold Coast

As our trip was winding down, we caught a bus from Tamale to Kumasi, the historical center of the Ashanti people. The landscape changed from flat savannah to lush, rolling rainforest, and the climate changed from coolish Harmattan dryness to hot and humid.

We caught another bus to Cape Coast on Ghana’s Gold Coast, where we stayed at the Mighty Victory Hotel for about $30 a night. Although it is located close to historical Fort Victoria, we were told not to go to the fort unaccompanied because “guides” were known to accost visitors and mug them if not hired.

Instead, we went to Cape Coast Castle, the point of embarkation for West Africa’s slave trade. We saw the dungeons where Africans who had survived the arduous journey from wherever they were captured were held until they were crammed aboard ships for their journey to Europe, the New World or the Caribbean.

During nearly 200 years of slave trading, West Africa lost an estimated 12 to 20 million of its most able-bodied men and women, most of whom perished en route.

Our guide had special words for the descendants of this massive diaspora: return to Mother Africa. See where your ancestors came from. Grow in the experience by coming to know yourself a little better. Pass this pride and identity on to your children.

The lessons learned in the castle also apply to a wider audience: come to know the mistakes of the past so as not to repeat them.

Our last few days were spent at the smaller nearby fishing village of Elmina, where we stayed at the Coconut Grove Bridge House (P.O. Box 175, Elmina-Ghana, West Africa; www.coconutgrovehotels.com), the nicest place we stayed on the trip. It is centrally located (across from Elmina Castle), with picturesque fish market/ocean views, and it has all the amenities, including an attached restaurant which is arguably the best in town.

Breakfast is included in the $50-a-night room charge, and free shuttle service to and from the swankier Coconut Grove Beach Resort, where they give you a towel and free use of the resort’s pool, is also offered. We spent several idyllic days working on our tans and swimming in the Gulf of Guinea.

Our flight didn’t leave until 10 p.m. on our final day, so we took a bus into Accra, Ghana’s sprawling capital city of two million. Normally, I avoid big cities like this, but I wanted to see the Centre for National Culture, reputed to be one of the best bazaars in West Africa.

It didn’t disappoint. There were acres of labyrinthine stalls with narrow walkways, and shopkeepers tried to outyell each other to get our attention. Several were overly aggressive, stepping in front of Jenna and forcing me to intervene.

Although it was a little scary at first, in quieter conversations they tacitly acknowledged that they knew they intimidated tourists. Despite all the yelling, an underlying civility and friendliness became apparent. And they did have some very cool stuff for sale.

We got three hours of serious shopping in before Abdul, a local restaurateur, called a taxi to the airport for us.

Reflecting on it

When I reflect on this experience, I am humbled by it. We in the tech world have so much in terms of food, housing, education and medicine, yet we often complain about the things we don’t have.

While not perfect, the West Africans I met, in their diverse human condition, go about their lives usually not complaining, except for the most dire of circumstances. I saw people who had next to nothing take great joy from the simplest of human pleasures: stroking a baby’s forehead while she napped or sharing a morsel of food with an elder neighbor.

The biggest disappointment we experienced was being unable to really connect on a personal level with any of the locals. Maybe we were just naive in this expectation. The nonconnect was more easily explained in the French-speaking countries of Mali and Burkina Faso where relatively few people speak English. But, almost invariably, those who did speak it did so with the intent of extracting money from us. I can’t think of a single instance in these countries where we were simply engaged as a matter of cultural exchange, except by other Europeans.

In English-speaking Ghana we did have a few satisfying casual exchanges, but they were clearly outnumbered by those seeking money.

I walk away from this experience conflicted by a cynicism arising from the nonstop attempts at being conned and by a desire to go back and volunteer in a place so desperately in need of help.

In my view, it is more dangerous being an American independent traveler today than anytime in my 40 years of independent travel.

In Ghana we usually said we were from Canada or Belize; being American sometimes triggered resentment and/or higher prices. In Burkina Faso and Mali, with their large Muslim populations, we said we were from Belize, for personal security reasons.

Preparation

Independent travel through this part of the world requires considerable preparation, unless you have unlimited time to learn as you go. While the rewards and life experiences are great, the going can get real challenging at times.

My preparation included reading Lonely Planet’s “Africa” and “West Africa” for an overview. For country-by-country specificity, I chose the Bradt Travel Guides to Mali, Burkina Faso and Ghana. Although Bradt does not use the fast-reading summaries that Lonely Planet does, each of the guides was invaluable and accurate for navigating these West African countries. The one exception was the Ghana guide (third edition), which understated restaurant and hotel costs by 30%-40%.

I also read “Africa — Dispatches from a Fragile Continent” by Blaine Harden. It explains why Africa is the way it is.

Additionally, I purchased Lonely Planet’s “French Travel Talk” and McGraw-Hill’s “Instant Recall French Vocabulary.” Both courses consisted of CDs and accompanying text.

In my opinion, if you don’t speak at least a little French, you may not want to attempt a trip like this. Most people in these countries are not used to travelers, do not speak English and tend to lose patience if they can’t readily understand you.

I created a detailed 29-day itinerary upon which flight schedules would be based. It included flight times/numbers, dates and places we expected to be arriving and departing, plus hotels. It all went on one piece of paper. I used this quick reference frequently.

The itinerary served as a time map to keep us roughly on schedule so that we could do all the things we wanted to do and still show up at the airport for the flight home, although we did deviate from it frequently, taking a little extra time here, shaving some time there.

Finally, most Europeans and North Americans will require visas to enter these countries. They can be obtained by downloading the visa application forms from the countries’ Internet sites (www.maliembassy.us, www.ghana-embassy.org and www.burkinaembassy-usa.org), filling them out and sending them with your photos, money orders and passports to the respective embassies in your country.

I used Federal Express to expedite this process, including a prepaid, self-addressed, return FedEx envelope for the embassies’ convenience and to assure that my passport was returned to me.

I would be happy to answer any inquiries sent to me c/o ITN.