Learning Mandarin at 76

This item appears on page 30 of the April 2015 issue.

After attempting to learn Spanish and Portuguese in many countries in Central and South America and taking a crack at Russian in Ukraine, I decided it was time to try Chinese, specifically, Mandarin. I knew that, at the age of 76, it would be a challenge, but what the heck?! You’re only young once.

Through the Omeida Language College (71-72 Longyue Rd., Yangshuo, Guilin, Guangxi, China; phone +86 0773 8827999, www.omeida.org), I got in touch with the coordinator Anya. In perfect English, she filled me in on all the particulars at the language school in Yangshuo. My trip to China would take place Aug. 29-Sept. 28, 2014.

Nobody gets into China without a visa. Anya sent me a packet of about eight pages, all in Mandarin, which I forwarded along with my passport to Visa Express (Houston, TX; 800/884-7579, www.visa

express.net). My passport came back with a multiple-entry visa in about six days.

My American Airlines flight direct from Dallas to Hong Kong took 16 hours. I stayed overnight at the SkyCity Marriott, then took a Dragonair flight to Guilin, China.

Anya had a modern taxi waiting for me, and 1½ hours later I was unpacking my gear at the Tiffany Hostel (No.4 Jiangjun Rd., Yangshuo County, 541900, China; phone 011 86 773 881 9500). My room was air-conditioned, with a large TV (with CCTV, China’s English-language news channel, on the screen) and a private bathroom with shower. I was beginning to think this was going to be a very pleasant month.

That same night, Anya told me to report to the Yangshuo college, one block away, to have dinner with the new students who would be learning English at the school. From there, one of the school coordinators walked with me and nine young Chinese women on a 2-mile trip to a restaurant in Xi Jie (West Street), a tourist area in Yangshuo. We sat around a huge round table loaded with food. This was a very friendly bunch of people.

During dinner, each girl would name some object in Mandarin. I then would repeat the word and give its name in English, and they would attempt to say the English word. It was lots of fun, especially when I attempted to use chopsticks. A waiter finally brought me a knife and fork.

The next day was Monday, the first day of class. My 24-year-old teacher, Andrea, had taught Mandarin for two years in Korat, Thailand. This was her first job teaching Western foreigners. She made the class fun, even though my American classmate and I gave her a hard time. She accepted our baby steps at learning Mandarin with good humor and grace.

Anya told me that I was going to have a partner to study with, a young Chinese woman studying English. It turned out that two 25-year-old women would be spending every evening with me. Grace was learning English in order to open her own business, and Joy, a computer software designer, was on loan from her company.

In the entire city, there were only about four taxicabs, but there were hundreds of motorcycles that everyone referred to as taxis. (The Mandarin word for them is motuoche.) You could find them at every intersection.

The motorcycles were very effective at wending their way through the most cumbersome of traffic. Each had a sturdily mounted umbrella that could be raised when it rained or when the sun got too hot. Each motuoche trip cost me about $2, although locals paid only $1.

Since Grace and Joy were in class each morning and my class didn’t start until 2 p.m., I would jump on the back of a motorcycle and ride to West Street for breakfast at McDonald’s or some other restaurant.

Every afternoon, I put Grace and Joy on the back of one motorcycle while I climbed onto another for the 10-minute trip to West Street, for which I paid the equivalent of about $4 for all of us. Needless to say, I was very popular with these drivers. One driver told Grace that I was very generous.

Every night we picked a different restaurant. Some nights it was German or French, and sometimes we visited a very modern Chinese restaurant where Grace had to make reservations. Restaurant prices varied from about $30 for the three of us to a high of about $50, which I paid.

The school guidelines for language partners specified one hour of conversation in the afternoon, since the students learning English have classes every night. Grace and Joy gave up their night classes, since they believed it would be more beneficial to learn English from a native speaker. (And it was not that they were looking for a free meal, since their meals were provided by the school and they were not that enamored of my choices of restaurants.)

The staff at the hostel, three young women, were also great fun to be around. One of them, Elaine, and then the other girls began to call me Grandpa, which — since I have 11 grandchildren — was not a foreign term to me. And, I have to say, they became my family for the time I was in China.

Every two days I took my dirty clothes to an amiable young couple in a home a half block away. They cleaned my clothes and ironed and hung my shirts and jeans on hangers for about $12 each time.

I was able to obtain Chinese yuan at an ICBC (Industrial & Commercial Bank of China) ATM about two blocks away, so I always had plenty of cash. Of course, it was difficult to spend much money, since everything in China seemed to be really inexpensive. (I tried obtaining funds from the Bank of China, but my debit card didn’t work there.)

One afternoon, while Grace and I were waiting for Joy outside the academy, my teacher, Andrea, appeared. Grace took her to a line of bicycles at the side of the building. When they returned, Andrea explained what had happened.

Andrea said there is an old Chinese parable about a family, a house and a bird. The family loved their house very much. One day a bird landed on the house, built a nest and became part of the house, thus the family ended up loving the bird too.

Andrea said that because she was my teacher, and because Grace loved me, Grace now loved Andrea, so Grace had just given Andrea her bicycle. This concept completely threw me.

Joy and Grace spent my third week in their home cities for some national holiday. Joy had not seen her parents for two months. For Grace, it had been two years. There’s a lot I do not understand about Chinese families, as well.

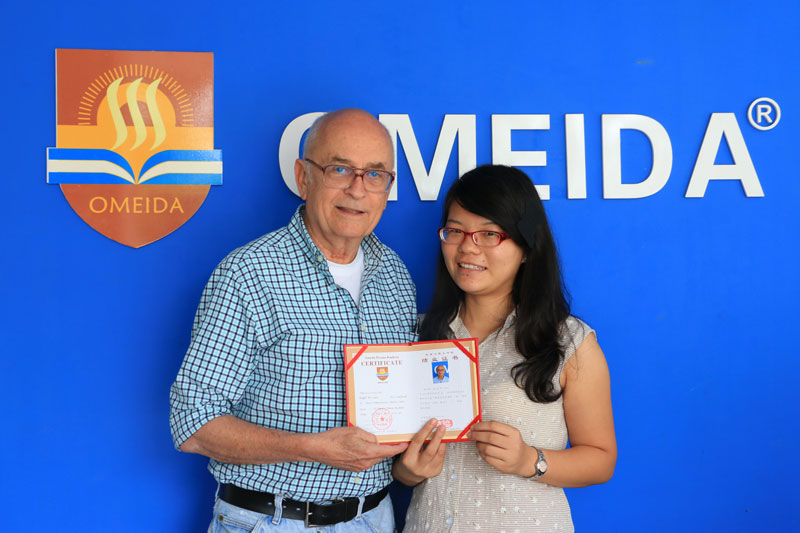

After a month’s schooling, I was given a diploma. The next day, a taxi took me to Guilin for my flight to Hong Kong and the next to Dallas.

I tallied my expenses for the entire trip. The visa cost $260. My flights from El Paso to Guilin cost about $1,660. My two overnights in Hong Kong (at a luxury hotel) cost about $600. The cost for the school — including education and room and board — was about $1,000. Restaurant meals, laundry and incidentals cost extra. Taxis in El Paso cost me about $70.

My food costs in China totaled $1,367. (I was charged for room and board, as the school furnished meals in the basement. If I was not going to have a meal there, I was supposed to tell them in order to have the cost subtracted from the total. The cost was so minimal, though, that when I did eat elsewhere, as I usually did, I never bothered to tell them.)

If you consider that, including transportation, the cost of any language school in Europe runs about $5,000, this school was a bargain.

I just want to say that the Chinese people I met in Yangshuo, a small town, were some of the nicest people on Earth, and I believe they have a bright future ahead of them. They want the same things Americans want: peace, plus an opportunity for them and their children to create a better world.

Anyone who would like more information on this school can email me at wtexas451@earthlink.net.

RALPH McCUEN

El Paso, TX