Cornwall’s Lost Gardens of Heligan

This item appears on page 58 of the May 2013 issue.

It was February 16, 1990. Only the tops of palm trees gave a hint of what might lay beneath. Workmen began to chop away with machetes at monstrous blankets of undergrowth, a 70-year accumulation of fallen trees, brambles, ivy and once-tidy boxwood hedges grown rampant into high, impenetrable walls.

Completely obliterated under the accumulated debris were acres of gardens laid out on land that came into ownership of the Tremayne family in the 1700s.

Squire Henry Hawkins Tremayne instigated the shape of the gardens in 1780. Three succeeding generations of Tremaynes nurtured and expanded his layout to create what was to become one of Cornwall’s grandest “show-off” gardens.

Reaching its heyday at the turn of the 20th century, themed garden “rooms” were designed to impress, showcasing shrubs and trees brought back from the far corners of the world by expeditions of plant collectors intent on procuring the rare, weird and beautiful. Extensive production gardens — vegetables, fruit and flowers — bountifully supplied the entire estate.

Then came World War I.

“Prior to the war, the estate employed 24 full-time gardeners,” Heligan’s head gardener, Mike Friend, told me during my May 2011 visit. “Of those, 16 went off to fight in the war. Only four survived the conflict.”

War’s end found a Britain changed forever. The idyll had ended. The old landscape of grand mansions, deference and cheap labor was no more. The Tremayne estate was not exempt. In the 1920s, the magnificent house was tenanted out; the last resident squire departed. With that, the glorious gardens gently went to sleep.

“In 1943, the Americans came to rehearse the Normandy landing.” Friend continued the story. “Officers were billeted here. Decay continued to settle in throughout the estate. At World War II’s close, a decision was made to sell the house.”

In 1990, the most recent inheritor of the 1,000-acre estate, John Willis, a Tremayne descendant, determined to take a look at “what went before” and put together an exploratory work force.

A gateway, obscured by a dense forest of bamboo, attracted their attention. Hacking through, they reached a small space, now known to be the Melon Yard, where cold frames and glasshouses once sheltered not only melons but such exotics as bananas and pineapples.

Inching forward, they discovered a cottage in a far corner with its roof caved in. A first find — the Thunderbox Room, with graffiti signatures of those who’d worked in the garden scrawled on a wall.

Nearby, another find — the head gardener’s office, the tea kettle still at the ready on the stove as if ready to pour.

“It was as if on a day in August 1914, everyone just stood up and left,” Friend said.

Today 20 gardeners work at Heligan, alongside two volunteers, nearing the number looking after the garden during its heyday.

“In homage to those who worked here long ago, we tend the gardens as authentically ‘period correct’ as possible,” Friend said as we set out together to explore Heligan’s two distinct areas: the Production Gardens, strung down the estate’s center, and their surrounding Pleasure Grounds.

We began in the Northern Gardens, following the “rides” (as Squire Henry Hawkins Tremayne called the gardens’ circuit of paths) as laid out in 1839. Giant rhododendrons, a century-old magnolia and towering camellias provided a springtime show over carpets of daffodils, snowdrops and cyclamen.

Continuing on the “eastern ride,” we came to the New Zealand area that received an infusion of new plants courtesy of New Zealand’s dismantling of its 2004 Chelsea Flower Show garden after its gold-medal win (Feb. ’12, pg. 58).

Nearby, Friend showed me the Crystal Grotto, its roof set with crystals: “On summer evenings, candles would be brought out. Imagine that twinkling display!”

“Victorian bee boles.” Friend identified the series of vaulted cells built into a wall close to the Production Gardens to ensure crop pollination.

Turning into the Production Gardens, an alleé of apple trees centered the Vegetable Garden with varieties chosen to ensure a parade of spring blossoms. There, as in the Flower Garden, “period correct” means everything from sourcing Victorian varieties as much as possible to labor-intensive double-digging to bringing seaweed up from the cove in order to dress the beds.

“We did, however, decide to garden organically,” Friend said, “and not follow the Victorian’s penchant for the use of such chemicals as nicotine and arsenic.”

Original greenhouses have been restored to their former glory. In the Flower Garden, Friend introduced me to Carly Holmes, the gardener in charge, who told me that she, for example, spends many an hour “with my little brush laboriously removing scale from the branches of fruit trees wintering over the glasshouses, and thinking, ‘What on earth am I doing?!’” She laughed.

I could have lingered for the remainder of the afternoon in the fascinating Production Gardens, but Friend wanted to show me the Ravine Rock Garden, where overgrowth had accumulated so deeply that no one remembered there had been a ravine. Cleared, it again resembles a walk through a mountain pass.

And then the Jungle, one of the last gardens built. There you see the largest collection of tree ferns in Britain, 60 varieties of bamboo, palms and conifers, rhododendrons and camellias, proteas, succulents, banana, kiwi and much more. Man-made watercourses connect four ponds. An attempt was made to re-create the original Georgian pathways — an effort abandoned in favor of a system of boardwalks.

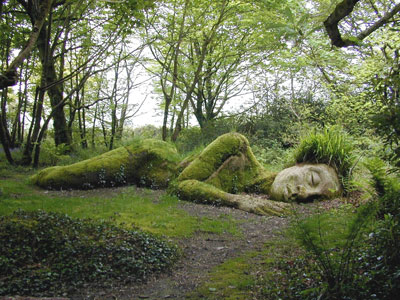

At the end of my tour with Friend, it suddenly dawned on me that I’d not seen the Mud Maid, a haunting photo of which had made me determined not to leave Cornwall without visiting Heligan, the Mud Maid’s home.

Friend took me to see her, deep in the woodlands. There she lay, exactly as pictured: not an old, fallen sculpture, as I’d surmised, but a commissioned work by local artists Sue and Pete Hill, brother and sister.

No matter! It was a fitting symbol for the Lost Gardens of Heligan: a sleeping beauty awaiting awakening.

The Lost Gardens of Heligan (Pentewan, St. Austell, Cornwall, PL26 6EN, U.K.; phone 0044 [0] 1726 845100) are open daily year-round, save for Christmas Eve and Christmas Day. Hours are 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. April to September and 10-5 October-March.

To find the gardens, from St. Austell take the Mevagissey Road (B32743) and follow directional signs to Heligan. Admission costs £10 (near $15) adult or £6 child (5-16), with children under five free. A guided tour (£1.50) is offered daily at 11:30 a.m., April-September.

Stout footwear is recommended, especially for those wanting to explore the Jungle and areas of the wider estate beyond the garden. With over 200 acres to explore, one could easily spend an entire day. The Willows Tearoom offers a seasonal lunch menu based on local products.