The search for the real Bali Ha’i

This item appears on page 61 of the January 2013 issue.

(First of two parts)

Bali Ha’i will whisper, on the wind of the sea, ‘Here am I, your special island. Come to me, come to me.’ — “South Pacific”

I grew up in Haiti and Thailand in the 1950s and ’60s, where we had no TV and only a record player for entertainment. As a kid, I listened to the record “South Pacific” at least a thousand times and was obsessed with the island paradise of Bali Ha’i — lush, exotic and populated with beautiful girls — which I was convinced was a real place. I wanted to live on that “special island” that was constantly calling, “Come to me.”

As an adult, I realized that the tale was fictional, but I was still obsessed. I read the original book, “Tales of the South Pacific,” by James Michener, read his autobiography and other novels, saw the play and movie and later the TV miniseries and researched the Pacific theater of World War II. I determined to solve the mystery of which island it was that inspired Michener to write about Bali Ha’i and to see for myself what it was like.

The evidence

To solve the mystery, I had to reexamine the “Tales” for clues.

As you may recall, the “Tales” state that the large island of Espiritu Santo in northwestern New Hebrides (now Vanuatu, about 1,000 miles north of New Zealand) is where the characters in the story are stationed. They are in a rear base, supporting the fierce battle against the Japanese on Guadalcanal, 500 miles to the northwest.

It is on Espiritu Santo that nurse Nellie Forbush meets and loves French plantation owner Emile de Becque. It is from Espiritu Santo that Marine Lt. Joe Cable sails across to the small island of Bali Ha’i and meets the beautiful Tonkinese (north Vietnamese) girl Liat, daughter of the famous, betel-nut-chewing “Bloody Mary.” Clearly, the fictional Bali Ha’i would be very close to the real Espiritu Santo.

The “Tales” say Bali Ha’i is a “small… neat… jewel-like” island, with “banyans, giant ferns, and… lovely gardens” and a small hospital run by French nuns. It is where the French authorities have hidden “all the young women of the islands” to keep them away from the Americans.

Bali Ha’i lies “within the protective arm” of a bay on the much larger “Vanicoro.” There is a narrow channel between Bali Ha’i and Vanicoro.

Unfortunately, Vanicoro is not a real name for any island in Vanuatu. It is described as being “large and brooding” and having four volcanoes, with lakes in one of the volcanoes. Cannibalism is still practiced there, and it has primitive natives who wear penis sheaths. Vanicoro is located “sixteen miles… east” of Espiritu Santo or (in one contradictory description) “south” of Espiritu Santo.

I studied maps and concluded that Ambae (also known as Aoba), about 30 miles east of Espiritu Santo, was the most likely model for Bali Ha’i. Ambae was, in fact, where the French hid the women of the islands from the Americans.

But there were problems with Ambae’s being the model for Bali Ha’i. It is not small and jewel-like; it is 25 miles long. It has no small islands next to it, so it cannot be Vanicoro, either. It has one large central volcano, not four (although it does have three lakes at the top of its volcano). During and just before the war, Ambae did not have any French nuns in residence, and it did not have cannibals wearing penis sheaths.

I noticed that Malakula, a large island south of Espiritu Santo, did have several small islands off its north shore, lying in a protective bay, facing Santo. Malakula also has a mountainous interior with tribes who wore penis sheaths and practiced cannibalism until the 1960s.

In 1994, still fascinated by Bali Ha’i, I wrote to Michener and proposed that, with his own touch of genius, he had taken Ambae and combined it with Malakula (as Vanicoro) and one of the small islands on its north shore and come up with the fictional Bali Ha’i. On June 8, 1994, Michener kindly wrote back through his aide and said that only Ambae was his primary inspiration.

Closer to paradise

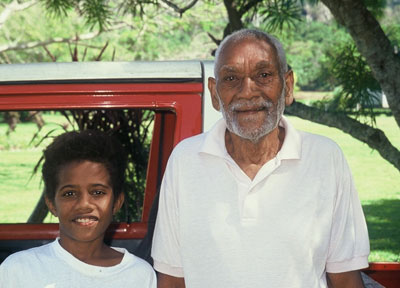

I had to go to Ambae. It took me a few years to organize my trip, but in 2001 I spent 10 days exploring the island, interviewing chiefs, residents and the governor and documenting the World War II experiences of the islanders. According to those with whom I spoke, virtually no other travel writers or explorers had been to Ambae and, despite its famous fictional name, it had been largely forgotten.

I confirmed many of Michener’s descriptions of the island.

He said that Bali Ha’i was dominated by a pig-killing cult, one in which the chiefs raised large pigs, knocked out their lower incisors and let the upper ones grow in a circular shape, then sacrificed the pigs in sacred ceremonies. I confirmed that this cult is still very important on Ambae and on many of the islands of Vanuatu, such that a circular tusk was placed on the national flag.

I found that Ambae was lush and tropical and could mysteriously disappear and reappear, as described in the “Tales.” It is usually obscured by a stream of dust and water vapor coming from a volcano on Ambrym island. This stream is usually blown north-northwest and prevents observers on Espiritu Santo from seeing Ambae. After a rainstorm washes out the stream or when there’s a major shift in the wind, Ambae seems to appear out of nowhere.

Also, Ambae’s single volcano is often covered by a “low-flying cloud” as described in the song.

Observations on Ambae

I stayed in “guest houses” (really, grass shacks) for a few dollars a night. I took utes (rusted-out open trucks) as taxis and found that there were no paved roads; the dirt roads were a series of giant potholes. Despite Ambae’s 10,000 residents, there were no hotels or tourist facilities.

All the population lived in small grass huts with corrugated iron roofs, and they worked as subsistence farmers, with cash incomes of only a couple of dollars a day each. But everyone I met seemed happy and cheerful.

I found a crashed, World War II, US fighter plane and was told that the pilot survived the crash.

I learned that the women of western Ambae are more Eurasian than those on other islands and was told that this may have resulted from French men intermarrying with the hidden women of World War II during and just after the war.

I found that malaria was endemic and that precautions were mandatory.

The island was lush, with rich volcanic soil, and, as was said in a song in the movie, there were “mangoes and bananas you could pick right off the tree.”

For a while I was content. I had found Bali Ha’i, solved the mystery and liked the reality.

But a few points still nagged at me. Where was the “small, jewel-like island”? Where were the cannibals, the penis sheaths, the French nuns and certain other elements? Were they all the products of Michener’s fertile imagination?

In June 2012 I took a posting in the office of the Prime Minister of the Republic of Vanuatu, working as a policy advisor in e-government. I determined to use that opportunity to explore my other theory about Bali Ha’i… by going to the mysterious island of Malakula.

Would I finally resolve my 50-year quest? Next month, I will tell you what I found there. I will even tell you how to get there by cruise ship!

Accessing Ambae

Conditions on Ambae are still challenging, according to the paramount chief of the island, whom I interviewed in October 2012. Roads are poor and malaria remains endemic.

Air Vanuatu has flights almost every day to at least one of the three grass airstrips on the island, and stays in local bungalows for about $20 per night can be arranged upon arrival or by calling the phone numbers on this page at www.positiveearth.org.