The Pamir Highway and the Five ’Stans — taking the road less traveled

by Bill Altaffer; San Diego, CA

I met my fellow travelers, a small group of Americans, in Almaty, Kazakhstan, to begin my third trip to the ’Stans, in September 2010. A third visit seemed necessary to comprehend the magnitude of Central Asia. This turned out to be the most in-depth, contrasting trip of all, arranged, as my previous trips were, by MIR Corporation (Seattle, WA; 800/424-7289). Their diligence and attention to detail helped create one of the best trips I’ve ever taken.

From the Tien Shan mountains to the vanished Aral Sea, we experienced the Five ’Stans as few travelers have.

Almaty

One of the largest cities in Central Asia, Almaty is nestled in the foothills of the Tien Shan mountain range and is the stepping-off point to the other ’Stans. It had been a major site on the Silk Road but was destroyed by the Mongols in 1211, leaving no traces of its ancient history. Today, it is a modern city made prosperous by oil and gas.

As part of a former Soviet republic, Almaty reflects Russian influences in language, architecture and demographics. With a population of over a million, it is spread out against the foothills.

I was amazed that the streets were washed down nightly, and, as we noticed everywhere throughout our trip, trash and litter were nonexistent.

Our sightseeing there included visits to a surprisingly interesting museum of ethnic musical instruments, the beautiful Zenkov Cathedral and an impressive World War II monument in the shape of the former Soviet Union (with the obligatory eternal flame). We also took a walk through Panfilov Park and an aerial cable-car ride to the top of Kok-Tobe, a 3,700-foot-high hill featuring a recreation area that overlooked the city and offered a fabulous view.

Before leaving Almaty, we drove into the Small Almaty Gorge, snaking upward approximately 5,000 feet to the Medeo Sports Complex. Set among the craggy peaks and alpine slopes created by an ancient glacier, this Olympic-sized skating rink has seen many world records set and was one of the venues of the Asian Games in early 2011.

Close to the complex, we had lunch in a traditional Kazakh yurt restaurant before setting off to Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan.

Into Kyrgyzstan

After a drive of several hours and a border crossing we arrived, immediately impressed by the abundance of trees in the city. At dinner in a local restaurant that evening, we were treated to an abbreviated performance of Manas, an epic poem celebrating the history of the nation. (Its full version can last three days.)

We were lucky to hear it performed by one of the best Manas singers in the country. I thought he would shatter my water glass with his voice!

We spent the following day visiting museums, walking through a park, participating in felt making and watching rehearsals for an upcoming military celebration — an accidental, unplanned event we happened upon.

That evening, we had the incredible experience of dinner in the home of the mother-in-law of my favorite tour manager, Paul Schwartz. It was a huge feast, including many exotic items and featuring vegetables from her garden. MIR Corp. trips regularly include dinners in local homes, one of the reasons their trips are so exceptional.

The following day we flew to Osh, located in the south of Kyrgyzstan. Situated in the fertile Fergana Valley, it is the country’s oldest (it celebrated its 3,000th anniversary in 2000) and second-largest city. We were the first MIR group to visit Osh since ethnic rioting in the spring of 2010 destroyed many Uzbek neighborhoods.

We visited the sacred Suleiman’s Throne, a limestone-and-quartz mountain with a view of the city. Recently declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, it is full of caves, some of which now house a museum. We also visited the local market, which had just reopened after the rioting.

Next we headed overland to Sary-Tash, a small village in the southern part of the country. This drive gave us our first taste of the mountainous terrain we would be traversing for the next several days.

Around Osh, the countryside was heavily agricultural and dotted with small villages. Many times, we had to slow to a crawl for the small herds of cows and goats in the road. As we approached the Pamir Mountains, the terrain became hilly, sparsely populated and rugged.

Sary-Tash is a collection of small houses and yurts close to the Tajikistan border. It sees few tourists. Its only accommodations are a few yurts with pads on the floor for sleeping, the lighting from bare bulbs powered by a generator. Bathroom facilities consist of an outhouse a short distance away.

Temperatures were cold and the food was very basic, emphasizing the fact that we had left the comforts of the beaten path behind and entered a world with rough conditions that few Americans can imagine. It was often uncomfortable, the food was occasionally inadequate, and the conditions were extremely basic, but, still, it was magical.

A journey to remember

After our somewhat uncomfortable night in Sary-Tash, we drove on rough, mostly unpaved road to the border post, where I had the funniest experience I’ve had in all my years of travel.

We disembarked from our van to stretch our legs while Paul went inside one of the buildings with the officials. We waited. And we waited. More than once I saw Paul, our local Kyrgyz guide and the outpost’s commander move from one building to another and back. The look on Paul’s face did not inspire confidence.

After a time, our driver moved our van back outside of the post’s gate, which was then locked in front of him. This was not encouraging. Finally, Paul came out to inform us of the situation.

Because of recent governmental instability, the country did not seem to have anyone in charge. It had been impossible to obtain the paperwork allowing our Kyrgyz driver (an ethnic Uzbek) to drive us across the 10-mile no-man’s land separating the two countries’ border posts. (If our driver had been an ethnic Kyrgyz, he most likely would have been allowed to drive us across after a baksheesh handshake.)

The commander offered to transport us in an army vehicle for the outrageous fee of $50 per person. Paul had bartered this down to $200 for all seven of us, but when he explained how this was to be done, we were incredulous.

All of us, with all of our luggage, plus the commander and a driver would make the trip in a small, Russian, jeep-like vehicle that could comfortably carry four. I thought there was no way that this was going to work, but, after several tries, all of our luggage somehow ended up crammed into the small space behind the backseat. I still don’t know how that was accomplished.

The commander then placed a tiny stool between the two front seats, where Paul perched with his legs scrunched against the gear stick. The remaining six of us crammed ourselves, sardine-like, into the backseat without a cubic inch of spare space. A couple of people promptly lost circulation in their legs due to people sitting on top of them.

We all were in strained positions but unable to shift at all, jammed up against Paul so that he was as uncomfortable as we were. Everyone was hunched, scrunched and barely able to breathe, while the commander and the driver occupied the two front seats, enjoying plenty of room and richer by $200.

The drive was very slow over rough, rocky road, across a riverbed and up and down steep rises, bouncing and jostling and seeming to last forever. Each bounce hurt more than the last, but I couldn’t stop laughing. Fortunately, other members of the group reacted in the same way. We laughed until tears came, though some of those tears could have been due to the pain of strained, bloodless limbs.

At long last, we reached the Tajik border post. As soon as the vehicle came to a stop, we exploded out of it like circus clowns, still laughing and knowing that we would never forget that ride.

Pamir Highway

We were met by two 4-wheel-drive vans and their astounded drivers. We loaded up, in much more comfort, and set out on the Pamir Highway. A highway in name only, it is a narrow, often-one-lane road, mostly unpaved, that winds its way through incredible scenery.

We had needed special permission to take this “roof of the world” highway. For many miles it paralleled the Chinese border, marked by a continuous electric fence that had been built by the Soviets.

We wound between mountains, eventually climbing over several high passes, including the highest, Kyzyl Art Pass, at 14,000 feet. For most of the day-long drive we were alone on the road, only occasionally meeting or passing huge Chinese trucks carrying goods to other parts of Central Asia.

This area is very sparsely populated, with only a few small villages scattered through it. We reached one of these, near the beautiful, pristine Karakul Lake, around lunchtime. Our lunch — unadorned pasta that had an “off” flavor — would have been considered inedible at home, but, at this point, it seemed quite good, especially looking back on it after some of the really bad meals we had later.

After an afternoon bouncing through more amazing scenery, we eventually reached Murgab. A town of about 4,000 people in the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region, it is a piece of disputed territory in the mountainous northeast corner of Tajikistan. Murgab, the highest town in Tajikistan, sits at the junction of three major roads and has long been a melting pot for the many ethnic groups of Central Asia.

We stayed in the best accommodations available in Murgab, a guest house, for two nights. Typical of guest houses in Central Asia, this was a home that takes in travelers. It included several outbuildings clustered around a small dirt courtyard, all enclosed by a fence with a heavy gate. The house had a few rooms, each with multiple beds for travelers, plus the family’s living quarters and kitchen. There was no running water, and electricity was available only for brief intervals in the evening.

The outbuildings included an outhouse and a sauna, where we were able to take bucket baths with its hot water. Also in the courtyard was an oven, where the woman of the house baked bread every few days.

Food there was basic and not particularly good. This guest house would not be for everyone, but our little group accepted and embraced the inconveniences and discomfort, knowing that we were experiencing the reality of life in that part of the world and that we could not experience the wonder of the area without enduring the hardships.

A dramatic drive

We spent most of a day driving out of the town and into a valley between two of the many mountains, climbing higher with each mile. We experienced what would be true for the next few days as we continued on the Pamir Highway: incredible scenery that can’t be properly described. The sheer majesty and immensity of the landscape left me amazed and filled with awe.

Many peaks were snow-covered and all were astoundingly dramatic — layers of rock in different colors pushed up, twisted and tilted, stabbing the sky. Combined with the afternoon shadows, the effect struck me as reminiscent of the background in Edvard Munch’s painting “The Scream.”

When we reached a point where the road had been washed out, we continued on foot, walking and climbing as far as we were able to go, eventually turning around when it began to snow lightly.

After returning to Murgab in mid afternoon, we visited the local market and a cooperative that sells handmade items to the few visitors who reach this remote spot.

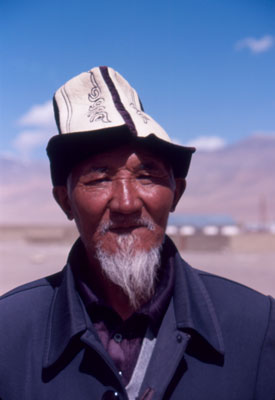

We were struck by the varied ethnicities of the people we met. Though we were in Tajikistan, many of the inhabitants of Murgab are ethnically Kyrgyz. Stalin had arbitrarily drawn border lines that carved up the area into the nations now on the map, with no regard for traditional boundaries or ethnic reality.

The following day we continued bouncing and crash-banging along the Pamir Highway, eventually reaching 15,270-foot-high Ak-Baital Pass. This day was much like many of the days to follow — long hours of driving on incredibly bad, dusty roads through some of the most fantastic scenery imaginable.

There were very few habitations along the way and even fewer places where it was possible to get even a bad bite to eat, but we hardly noticed the inconveniences. Our senses were filled with the ever-changing views of peaks, valleys, narrow waterfalls, vegetation, colors and textures that we experienced as we climbed slowly up and down the narrow roads snaking through the mountains.

Khorog

Eventually we arrived in the city of Khorog, the capital of the region, where we spent two nights. Khorog is located in one of the poorest areas of the Pamirs. In spite of that fact, it is a thriving city and home to a University of Central Asia campus. The university is underwritten by the Aga Khan Foundation, which also supports many other businesses and charities in the area.

Our hotel, the Serena Inn, was very nice by any Western standards. It had been built by the Aga Khan on the bank of the Panj River with a view of Afghanistan on the opposite bank, perhaps only 50 yards away.

We spent a full day seeing the sights of Khorog, including the world’s second-highest botanical garden and the first motorized vehicle to traverse, in 1932, the Pamir Highway, a small pickup truck displayed at the edge of town on a large concrete block.

Before departing Khorog, we stopped at the Afghan market where Afghanis peddle their wares, some of which were handmade but many more of which were manufactured in China.

We spent the next two days climbing over more mountains on some of the roughest, dustiest roads in the world. All of the first day the road snaked along the Panj River, the natural border with Afghanistan.

The scenery was continuously changing as we wound our way carefully on the narrow roads, sometimes with only a couple of feet to spare as sheer cliffs dropped away on one side, the mountain wall mere inches from the other side of the vans.

Narrow footpaths zigzagged up the steep slopes, interrupted often by rubble from landslides. Frequent waterfalls, narrow but very tall, dotted the view. The very few tiny settlements there are situated alongside these water sources, perched on a few small, flat spaces of land alongside the road. To me, the living conditions in these locations appeared little above that of a caveman.

Moving toward luxury

Close to nightfall on the day we left Khorog, we arrived at the little village of Kalaikhumb, where we were fortunate to stay in a guest house supported by the Aga Khan Foundation. It was very basic but updated in ways other guest houses in the region were not. It had electricity, its courtyard was concrete rather than dirt, and it boasted a real bathroom with a flushing toilet and a tub with hot, running water. As usual, these facilities were located across the courtyard from our second-floor guest quarters.

Toward the end of the next day, we eventually found ourselves out of the mountains and on real roads as we approached Dushanbe. While still outside the city limits, we stopped to pay local boys to wash our vans using water from a small stream. Dirty vehicles are ticketed in Dushanbe, so several groups of boys perform this service for a small charge. Before the wash, our vans could not have been dirtier.

We then experienced the shock of returning to civilization with its traffic and crowds of people. We eventually arrived at another shock, the five-star Hyatt Regency in Dushanbe. After our rough accommodations on the road, this was mind-boggling — one of the nicest hotels I have ever stayed in.

Since we could have grown crops in the dirt and dust we had on our bodies and our luggage, we felt very out of place checking into this clean, ultramodern, luxurious establishment. A hot shower soon had me feeling quite comfortable and ready to enjoy being pampered.

I was bemused by the contrast between sleeping on the floor of a yurt with no running water at one end of the Pamir Highway and ending up at the other end in a true five-star hotel with all the amenities, including a lap pool. We spent two decadent nights there while we explored Dushanbe, feeling that we had earned the right to enjoy the upgrade.

Uzbekistan

Leaving Dushanbe, we flew to Khujand, then spent the rest of the day driving across the border to Samarkand, Uzbekistan. Crossing the border was the usual ordeal in this part of the world, with us hauling our luggage across wide expanses of no-man’s land and completing multiple copies of Customs declarations, all of our documents repeatedly being examined on both sides of the border.

We spent two nights in Samarkand, a bustling city with much history and many sights to see, including the Registan, ringed by an incredible collection of Timurid architecture, and the Bibi Khanum Mosque, built by Tamerlane to be the largest mosque in the Islamic world. We also strolled through the fascinating Shah-i-Zinda, a collection of tombs and mausoleums, and visited Gur-Emir, the location of Tamerlane’s tomb.

On the 16th day of our trip, we traveled by bus west to Bukhara, an ancient Silk Road oasis for camel caravans. Uzbekistan differs from the other countries of Central Asia in that it contains a number of very old cities.

The ancient architecture and design in Bukhara have been better preserved than in other places (despite being heavily bombed by the Bolsheviks), resulting in a charmingly lovely and exotic city.

We visited the Zindan (prison) with its infamous “bug pit” where two British emissaries, charged as spies, were brutally imprisoned in the 19th century during the struggle between Britain and Russia for influence over this strategic oasis. We saw the Kalon Mosque and Minaret, the second-largest mosque in Central Asia, its minaret ringed by 14 unique bands of brickwork.

We stayed in a delightful “boutique hotel,” Sasha & Son, in the old Jewish Quarter. It had been fashioned from several old merchant houses and decorated in the national style.

It was easy to walk from the hotel to Lyabi-Hauz Plaza, the central pond and meeting place of the Old City, where we found an amazing array of unique handicrafts and unusual ethnic items to satisfy even the most discriminating shopper. Paul told us that this is the one place where travelers often realize that they did not bring enough cash.

Turkmenistan

After our pleasant stay in Bukhara, we spent another day traveling, first driving to Türkmenabat, Turkmenistan (our fifth ’Stan), then flying on to Ashkhabad.

Ashkhabad had been destroyed by Mongols in the 13th century. In 1948, a massive earthquake ravaged the rebuilt city, killing, by some estimates, over two-thirds of its population. Lately, it has seen a major building revival.

The city had changed dramatically since my previous visit over a decade ago. The look of the city is spare-no-expense ultramodern, though most of the luxury apartments and fancy hotels seemed to be unoccupied. Huge parks and statues complete the picture of a country suddenly dripping with natural gas revenues.

Fortunately, we were able to visit a local market outside of the city for a taste of reality. The Tolkuchka Bazaar is one of the most exciting open markets of Central Asia. Its name literally means “lots of elbowing.” In spite of the huge crowd of people, we enjoyed experiencing a market that has been attracting merchants and shoppers from all over the country for hundreds, maybe thousands, of years.

In town, we toured the Lenin Monument and the incredibly lavish mausoleum of Turkmenbashi, which is modeled after Napoleon’s mausoleum and is located next to a sparkling new mosque, an eye-popping showplace rather than a dedicated place of worship.

Back to Uzbekistan

The trip officially ended in Ashkhabad. However, some of us stayed on for an extension that started with a return to Uzbekistan for a one-night stay in Khiva.

Khiva is a living museum, including the Djuma Mosque, with its more than 100 carved wood columns that create a forest-like effect. Four of these columns, older than the rest, show fire damage, supposedly from Genghis Khan’s torching of the city.

Next we drove to Nukus, the capital of the autonomous region of Karakalpakia (or Karakalpakstan) in western Uzbekistan. The Karakalpak people are more closely related to the Kazakhs than to the Uzbeks, with a mix of tribal bloodlines.

Nukus sits at the center of an area crisscrossed by old caravan routes and dotted with ancient ruins. Its claim to fame is an amazing thing to find in such a remote area: the Karakalpakstan State Museum of Art, the “Louvre of the desert.”

It is famous for the Savitsky Collection, a huge collection of avant-garde Russian art. Igor Savitsky amassed the collection, much of it banned by the Soviet regime and smuggled out during Stalin’s leadership. It is an astonishing world-class compilation of incredible art of all mediums, well worth the ordeal of getting to Nukus to experience. However, for us it was an added bonus.

Our main purpose in going to Nukus was to take an all-day bouncy trip to Muynak, once a thriving fishing port on the Aral Sea and now not much more than a ghost town. We wanted to see the remains of the Aral Sea, formerly the fourth-largest inland sea in the world. It barely exists today after the Soviet diversion of its two feeder rivers, the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, for agricultural irrigation. Muynak is now hundreds of miles from any remaining water, water which now is too salty to support life.

The magnitude of this ecological disaster is impossible to comprehend. Among the rusting hulks of old fishing boats and freighters, we spent time walking on the sands that used to sit under some 40 to 50 feet of water. It was an eerie experience that I won’t soon forget.

Coming to an end

Finally, we flew to our last city, Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan. This is a lovely, modern city which, like Almaty, where we had started this adventure over three weeks before, is located at the foot of the Tien Shan mountains.

Tashkent dates back to, perhaps, the fifth century BC. Unfortunately, much of its historical architecture was destroyed in a massive earthquake in 1966. Now, wide, tree-lined boulevards flanked with name-brand Western stores are interspersed with beautiful parks, fountains, monuments and statues. It is truly an international city. I wished that we had more time to explore it properly.

In retrospect, this amazing overland trip across the Five ’Stans was one not only of extreme contrasts but of learning. The experiences we had, the cultures introduced to us and the vast scenery we traversed gave us a perspective on man’s origin and his adaptations for survival. We got a taste of how little people need in order to live and how difficult it is to live directly from the earth.

We were reminded that much of the world does not live in the fast-paced, convenience-filled style to which we are accustomed. It was humbling.

This is not a trip for inexperienced travelers. However, if you can handle roughing it at times, have become jaded by easier travels and want to see some awe-inspiring, dramatic scenery, it might be for you.

Our customized trip cost around $10,000 per person, including our visit to the Aral Sea. International airfare cost extra. MIR has since added a similar, 18-day itinerary, “The Pamir Highway & Across Fabled Frontiers,” which is priced at $6,995 per person, double (4-12 travelers).

Be sure to take toilet paper, antibiotics, chewable peptoids and, if you like shopping for exotic, beautifully made handicrafts available nowhere else, much more cash than you think you will need.

If you have not seen Central Asia, you are missing a huge chunk of the history, culture and natural beauty of this Earth.