A 23-day exploration of Ethiopia

by Yvonne Horn, Santa Rosa, CA

Nothingness stretched seemingly forever as viewed from my window seat aboard the Ethiopian Airlines Fokker 500 turboprop en route to Bahir Dar from the country’s capital city of Addis Ababa. Nothingness, that is, if one discounts the ferocious landscape of deep canyons and jagged tumbled mountains unfolding below and the now-and-then-glimpsed handful of tiny communities of tukuls, circular dwellings perched precariously on barren plateaus. No roads — only occasional barely discernible trails as thin as pencil marks indicated the comings and goings of humanity through this harsh convulsion of spectacularly beautiful ruggedness.

“Discovering” Ethiopia

I had considered myself somewhat of an adventurer when I signed on to explore Ethiopia with Toronto-based ElderTreks (800/741-7956, www. eldertreks.com), but my adventure would not hold a candle to that of Irish writer Dervla Murphy, whose account, “In Ethiopia with a Mule,” I’d read as I prepared for my journey.

In 1966, Murphy set out to walk north to south across Ethiopia’s highlands alone — save for her faithful, gear-carrying companion — climbing jagged ranges, dipping into formidable gorges and creating astonishment as she appeared almost as if an apparition at such isolated collections of tukuls as I was seeing below. Four months later, at her final destination of Addis Ababa, her pocket pedometer read 1,024 miles.

So what prompted my decision to visit Ethiopia? My answer is short and clear: an ElderTreks catalog arrived in my mailbox. With a flip of a page, “Ethiopia, the Horn of Africa” stopped me dead in my tracks with the realization that here was a place that had completely escaped my insatiable, off-the-beaten-track wanderlust radar.

Armed with stacks of library books, I began to read of a complex country, one which was historically and culturally unique. Not really Africa but not quite Arabia, it is timeless and remote, a place where familiar basics stand on their heads — including a calendar with a “13th month” and the millennium scheduled to be celebrated on September 11 of this year. Yet, it has been a victim of drought, terrible famine and civil disruption, with visible remnants of decades of war and extreme poverty, all of which have kept outsiders at bay for years.

Delving deeper

Ninety-eight percent of the relatively few travelers who make their way to Ethiopia confine themselves to the well-defined northern Historic Route. They fly to four cities, each distinctly different from the other: Bahir Dar, Gondar, Lalibela and Axum. The route encompasses such cultural and historical treasures as the birthplace of the Nile; monolithic churches carved out of pink granite; towering stelae; the reputed resting place of The Ark of the Covenant, and the pool where the Queen of Sheba supposedly bathed. Having done so, those 98% return to Addis Ababa and fly on home.

Not so for those traveling with ElderTreks. Half of our itinerary of 23 land days would be devoted to the well-deserved historic north. The other half — heading out from Addis Ababa via Land Rovers — would take us into a different Ethiopia, the tribal south.

ElderTreks specializes in adventure travel designed exclusively for people 50 and over. For this February ’07 trip, 14 intrepid travelers met in Addis Ababa, most arriving from far-flung U.S. cities with but two from Canada. Our ages spanned three decades. We all were walking medicine chests, everyone having followed ElderTreks’ health precaution suggestions. The group was primed to expect high-altitude days of over 9,000 feet, an activity level of “3” (“moderate” on Eldertreks’ scale of 1 to 5) and long drives over rough, dusty roads and tracks.

We met at the Ghion Hotel, the flagship for the eponymous chain of gone-shabby, decades-old government hotels in which, for but one night, we would stay throughout the north. Tolerable for its surrounding large garden and central location, the hotel claims a fine Ethiopian-style restaurant specializing in Ethiopia’s oh-so-tasty national food, injera, a large, pancake-like bread.

Seated around small, hourglass-shaped baskets that served as both dining tables and serving plates, we waited to sample the traditional meal. Our server first came around with a pitcher of warm water and a basin for rinsing our hands. Then arrived the large pancake made of tef, a nutritious grain unique to Ethiopia, sized to drape over the table. On it was placed piles of wat, spicy vegetarian or meat stews. One tears off a piece of the “tablecloth,” mops up a portion of wat and pops it in the mouth.

We delighted in this type of meal during our journey as it was a relief from generally uninspired cuisine. A surprising alternative was the invariably present option of tomato sauce-topped spaghetti (but, remembering Italy’s 1936-1941 occupation of the country under Mussolini, perhaps it is not that surprising at all).

Rewarding innovation

We were off to Bahir Dar in the north, located on the shores of Lake Tana, Ethiopia’s largest lake and the source of the Blue Nile. Bahir Dar is the base city for visits to both the Blue Nile Falls, pictured on the one-birr note as it was before a hydroelectric plant drastically reduced its magnificence, and the more than 30 monastic churches located on the islands and shores of Lake Tana, many dating from the 14th century.

Arriving at the gateway path to the falls, we were suddenly overwhelmed with dozens of would-be “guides.” Our Eldertreks guide Yvette immediately took charge; it helped that she was a known entity from previous ElderTreks visits. Three “official helpers” were hired, Yvette making certain they were not the same ones hired before. It was a strategy that worked, with varying success, throughout our journey.

As in every third-world country, poverty tugged at the heart both in the north and south, but it was suggested we give money only for a requested service or item. The going rate for a helping hand down a rocky path was one birr, the equivalent of eight cents, and in the tribal south a payment of two birr was recommended for a photo of an individual. Nothing would be given for cries of “You! You! Money! Money!” As our national guide, Tsegaye, exclaimed, “This is not our culture! We are not a nation of beggars!”

In the south, young boys would appear from nowhere at the sound of our approaching Land Rovers, some with an endearing “act” — walking on terrifyingly high stilts or performing backward cartwheels worthy of an Olympic gymnast — or something to sell, like the young man holding forth an enormous bouquet of jacaranda or the group of youngsters decked out in wooden, make-believe sunglasses. Yes, peel off a birr or so.

We carried boxes of gifts into the south, presenting them at the end of tribal visits. Oddly, it was the men of the villages who gathered about, creating an endearing picture of rather ferocious-looking characters dressed, or undressed, in skins, shells and beads and intensely involved as Yvette pulled out and demonstrated, for example, the use of a mosquito net, “For the babies,” with the men nodding their understanding.

Orthodox Ethiopia

Unlike Dervla Murphy, who slogged waist deep in mud and reeds to circumnavigate the shores of Lake Tana, we had a boat waiting at our hotel dock to take us for a day devoted to the lake’s monastery churches. Here began our immersion into the mystery and legends of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

Christianity, introduced here in the fourth century, took distinctive turns in Ethiopia. In medieval times the country, known then as Abyssinia, was the legendary domain of Prester John, a Christian priest-king said to rule a world of unicorns and pygmies. This caught the attention of the Portuguese and is considered to be, at least partially, the reason for their arrival in Ethiopia in 1520. Today, not quite Coptic but most certainly not Western, the resulting religion nestled in the isolation of the highlands continues on its individualistic way.

We visited four of Lake Tana’s churches, following woodland paths chattering with monkeys, chirping with birdsong and offering enticing glimpses of village life along the way. Monks draped in shammas, wrappings of white cloth worn by men and women alike throughout the north, awaited piously at the entrances.

The churches, round in shape and made of chicka, an adobe of mud, straw and dung, revealed interior walls and ceilings swarming with naïve, brightly colored murals bursting with angels and stories from the Bible.

Lalibela

Churches are the predominant theme of the historical route, each stop on our flying hopscotch introducing us to more. While many merged into memory, indelibly imprinted are those of Lalibela, one of Ethiopia’s most gorgeously located communities, perched among wild, craggy mountains and vast rocky escarpments.

The red carpet was out at Lalibela’s airport. Not for us, we quickly realized, but for the elaborately garbed priest who had occupied the front row of our Fokker 500. The Patriarch of the Eastern Orthodox Church had arrived. The reason for his visit — the dedication of European Community money to aid in the restoration of what are undoubtedly wonders of the world.

Under the direction of King Lalibela, 11 monolithic, beneath-ground churches were carved in the 12th century out of solid granite. Craftsmen from Syria, Greece and India (legend adds angels to the list) constructed the marvels in 23 years.

Trenches and courtyards ring the churches, providing space for stone graves and hermit cells. Tunnels and passages provide connection to individual churches, each unique in shape and size. Aided by local guides, we would spend the better part of two days making our way through them.

Immediately upon our arrival in Lalibela town, we joined a shamma-draped throng gathered in a central courtyard where double rows of chanting priests and deacons, staffs in hand, swayed in precise rhythm to the vigorous beating of drums and ringing bells. The Patriarch and his richly robed priestly entourage, shaded by gumdrop-colored silk umbrellas covered with sparkles, presided over all. Piety, fervor, spectacle — so it has been in Lalibela for at least 900 years.

Plethora of treasures

While churches of ancient Christian kingdoms are the undisputed foundation of the northern route, ElderTreks’ itinerary embraced more. In Gondar, the first capital city of the Ethiopian Empire, we visited the Royal Enclosure, a walled compound of 17th-century castles, and continued on to the elaborate bathing pool attributed to Emperor Fasilidas.

A full day’s excursion out of Gondar took us into Simien Mountains National Park, a place of deep gullies and amethyst-colored mountains with some of Africa’s highest peaks. There we picnicked on an overlook in the company of gelada (bleeding heart) baboons.

Outside Axum, we looked over the surrounding hills of Adwa to where Emperor Menelik II defeated the Italian army on March 1, 1896, ensuring that his empire would be the only African state to enter the 20th century as a fully independent entity.

A gracious invitation to come for coffee at a Lalibela private home introduced us to Ethiopia’s beloved coffee ceremony that includes scattered flowers, the roasting and grinding of beans, wafting of incense and the passing of woven trays of roasted barley and popcorn before culminating in multiple rounds of coffee being sipped from small, handless cups.

In Axum, at the town museum, we viewed an archaeological treasure trove displayed in the most ordinary of glass cases — some even leaning against walls — that included rock tablets inscribed in a variety of languages, an array of Axumite household artifacts, crosses, coins and a 700-year-old leather Bible.

We visited Axum’s field of some 75 stelae, the erection of the largest, towering at 23 meters, traditionally credited to the mysterious power of the Ark of the Covenant. That of greatest national pride, however, lies sheltered under a tin roof, cut into pieces for its finally negotiated 2005 return from Rome, where it had been taken by Mussolini.

Seeing these treasures being stored in such seemingly haphazard ways astounded me, until I remembered that they are the treasures of a country counted among the poorest on Earth.

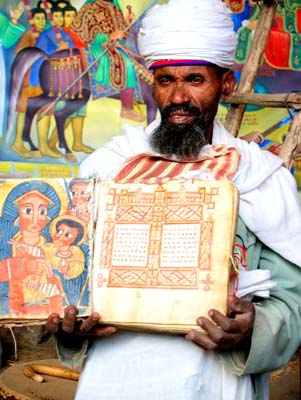

Priests opened centuries-old, illustrated vellum Bibles for our inspection and then casually covered them with a piece of tattered cloth. Lengths of what looked like discarded bedspreads protected the most sacred and ancient of art. Simple padlocks secured an assortment that included jeweled crowns displayed in a little rectangular outdoor shed — and on it went.

While numbered among the world’s poorest — with an average yearly income of only $120 — Ethiopians must also be counted among the Earth’s most dignified, proud, innately courteous and kind, let alone handsome.

“They are the reason,” said Yvette, “that I return time and time again.”

Addis Ababa

Boarding our last Fokker 500 flight, we left Axum for Addis Ababa, where Land Rovers were waiting to take us into the south.

This would be my second visit to the capital, as I had flown into the city at the beginning of my trip. Whenever possible, I fly the national airline of my destination, hoping to capture en route a bit of the culture. Ethiopian Airlines (www.ethiopian airlines.com), with its every-other-day schedule departing only from Washington Dulles Airport, presented a problem. With my departure city being San Francisco, I had overnighted at the conveniently located Marriott Dulles Airport hotel (www.marriott.com/hotels) in order to mesh with Ethiopian’s schedule (and to break an otherwise grueling 24-plus hours of travel), arriving in Addis Ababa a day in advance of the group.

As a group we were scheduled to tour the National and Ethnological museums, considered the best of their types in Africa. Setting those aside, I ventured on my own into a city of almost overwhelming contradictions that only began with shepherded flocks sharing boulevard space with motorized congestion.

My attempts to gain some understanding of Addis included a hired-car drive through a suburb of shacks, continuing high into the Entoto Hills for a view over the city; a walk through a small corner of the Mercato’s vast cacophony of stalls, kiosks and shops; a stop at the coffee shop Tomoca, beloved for its Italian atmosphere; a tour of Haile Selassie-built Africa Hall, where an enormous stained-glass mural depicts Ethiopia, past, present and future, and a visit to Asni Gallery, hidden away on a dusty side street, for its fine display of Ethiopian contemporary art.

With all that, my assessment coincides with one guidebook’s suggestion that with one day in Addis, you should do thus and so. With two days, do day one slower.

Now, returning to the city from the north, the second half of our adventure awaited. “Into the south,” as it was invariably referred to by Yvette, invoked a picture of standing on a diving board ready to plunge into the unknown.

The south

Philip Briggs, in his excellent Bradt guidebook “Ethiopia” (www.bradt guides.com), writes that nothing in highland Ethiopia prepares one for the south, a region of extraordinary cultural integrity inhabited by colorful and defiantly traditionalist people virtually untouched by outside influences.

Along with 400 liter bottles of water, we piled into five Land Rovers each top-racked with four drums filled with 25 gallons of gas. Tsegaye, outfitted for the occasion in a jaunty safari hat, introduced our drivers, Yared, Yonas, Wendimu, Hailey and Dagnew, with Yvette adding, “As you will see, they are literally our lifeline.”

Garamo, who would cook for us during our days in tents, prepared to follow in a van loaded with food and camping gear.

Addis’ industrial suburbs and adjoining small communities continued for miles as we traveled south. With one hand on the horn, our drivers made their way through an endlessly fascinating parade of humanity and animals — women bent like question marks under unthinkable back-burdens of fuel and fodder; men encouraging donkeys to move along; children dressed in school uniforms either coming or going, and herds of cows, sheep and goats.

Those of you wondering where old foosball games retire, look no further. Every settlement, north and south, had at least one set up at roadside in the shade of a tree.

At last we entered a land of open savannah, acacia forests, fertile fields, scattered lakes, soft hills and towering mountains. Long before, asphalt had given way to potholes and dust (fewer than 15% of Ethiopia’s roads are paved) of which we’d been given fair warning in Eldertreks’ brochure. A hand-drawn map of our southern itinerary gave both mileage and distance between destinations, emphasizing “travel times are underestimated.”

Our days in the south included a boat trip on Lake Chamo to view its rich population of stilt-legged waterbirds, log-like crocodiles and hippos wading up to their eyeballs.

We had Nechisar National Park, with its herds of zebras and gazelles, all to ourselves, save for the surprise of a colorfully garbed party of four native people emerging from the bush, one carrying a rifle, another a pink parasol.

Lake Awassa’s “fish market,” a gathering of 100 or more rowboats used for fishing, featured mountains of tilapia, much of it gutted and enthusiastically eaten raw on the spot by the gathered populace.

We crawled into pup tents at Mago National Park for a night warily listening to the snorts and rustlings of the park’s checklist of close to 100 mammal species. Our 3-night stay at the campground at Turmi featured the relief of stand-up-inside tents and, at night, with a full moon floating in the mango trees, the chanting and singing from a Hamer village right next door.

Tribal visits

One afternoon we were invited to visit the village, a collection of a dozen or so tukuls inhabited by striking and dignified people. The women color their plaited hair with red earth and butter and wear skirts of elegant leather decorated with cowries, a dozen or more copper bracelets fixed tightly on their arms. The men, some with their hair done up in a topknot to indicate that they had killed a person or dangerous animal within the year, don what looks to all the world like miniskirts.

Long drives through landscapes of incredible diversity introduced us to more tribal groups: the hardworking Konso, excelling as cultivators on elaborately terraced mountainsides, the women wearing ankle-length striped or solid-colored cotton skirts with a surprising ruffle bustle; the Karo, an endangered people (numbering fewer than 600) noted for their exuberant body painting, and the Mursi, one of the most original and eccentric of the native peoples, specializing in body scarification, its women one of the last groups in Africa to wear large plates in their lower lips.

The tribal visits were fascinating but also troubling, nowhere more so than with the Mursi. It was troubling on both sides: for the tribal women displaying aggressiveness that they be the one chosen for a photograph to earn two birr, and for us, whose reason for photographing them was their bizarre differentness — cultural identity turned sideshow. Longed for was the opportunity to learn about them — their houses, ceremonies, rituals and social activities. That happened but once.

Dramatic switchbacks took us into the fertile mountainous land of the Guge hills, home of the Dorze people, renowned weavers. The shamma cloth produced here is regarded as the finest in Ethiopia.

We were met on the road outside the village by the young English-speaking headman who, after greeting Yvette warmly, ushered us into a Dorze “Williamsburg.” In an area set aside from the main village, one of their distinctive beehive-shaped houses was open for inspection. Inside, spinning and weaving were demonstrated along with the amazing number of uses for false banana.

In a central area, we gathered around as the kids of the village played instruments and performed the Dorzes’ distinctive hip-wiggling dance. A group “entrance fee” paid in advance included unlimited photography. Ah, if all visits — satisfying both sides — could have been so.

Final impression

On noncamping days, accommodations for the most part were “iffy,” with one notable exception, Aregash Lodge. Here, 12 bamboo-thatched tukuls surrounded by coffee fields and lush forest provided downright luxury while paying attention to traditional style. Produce from the lodge’s organic garden assured the trip’s most superb dining experience.

Paths tying Aregash to its neighbors allowed the opportunity to casually walk and greet others along the way. At night, hyenas howled and jackals roamed.

At our orientation meeting in Addis Ababa, Yvette promised, “With this trip, you will have seen Ethiopia.” Not quite so.

We’d not visited the walled city of Harar in the far east nor the harsh Danakil region in the north, where Lucy and her hominid predecessor had been uncovered — and my list could go on. Even so, we’d seen far more of Ethiopia than had Dervla Murphy on her incredible walking journey into the north.

I’m invariably asked if I would go back. Probably not. Am I glad I went? Unequivocally, yes!

Money matters

The current land price for ElderTreks’ 23-day tour of Ethiopia is $5,295 per person (double occupancy), an inclusive fee covering “best available” accommodations (four days camping), meals, service of local guides, porter and guide tips, and transport within the country.

Travelers should be aware that Ethiopia has no international ATMs and that credit cards are not widely accepted. My advice is to bring sufficient cash to change into birrs, which most hotels are equipped to do.

Yvonne Horn was a guest of ElderTreks, which covered the land portion of her scheduled tour.