The Gobi Desert — On the trail of Genghis Khan

by Herschell Gordon Lewis, Ft. Lauderdale, FL

We certainly weren’t about to travel all the way to Ulan Bator, Mongolia, without expanding the adventure to include the Gobi Desert.

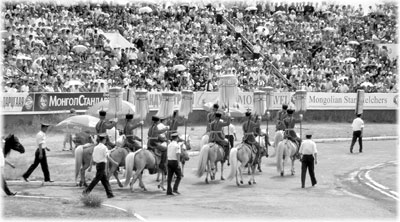

In July ’05, my wife, Margo, and I had boarded the Trans-Siberian Express in Moscow, traveling for eight days across Russia and Siberia and arriving in the capital of Mongolia in time for the annual Naadam Festival, the celebration of athletics such as archery, horse racing, wrestling and a strange event called anklebone shooting.

As exciting as the opening ceremony of the festival was — with as many Westerners in the packed stadium as locals — and as fascinating as anklebone shooting (flipping a 2-inch flat disk about 10 feet to hit two tiny dice-size bone fragments) turned out to be, it was all just a prelude to the Gobi.

Indigenous accommodation

Leaving the plush Chinggis Khaan Hotel, flying on the relatively new Aero Mongolia Fokker 50 to an airstrip outside the remote town of Dalanzadgad and riding in a jouncy Russian-built Jeep-like vehicle to our first accommodation in a ger camp, we knew we weren’t in Kansas anymore.

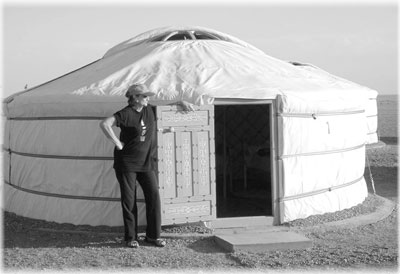

A round, felt-lined temporary residence anywhere from eight to 12 feet in diameter, a ger is normally equipped with beds, some tables and not much else. No ger we saw had water, which means no plumbing. Sometimes a single electric light had been wired into one of the two center posts that supported the top, sometimes not. The round shape with its tapered top proved remarkably capable of deflecting the often forceful desert winds.

The word “ger” is particular to Mongolia, and the same basic shape and materials haven’t changed for about a thousand years, except that concrete foundations covered with linoleum or wood floors have supplanted dirt floors. (In Siberian Russia it’s called a yurt, but calling it that in Mongolia is a faux pas.)

A major benefit is that nomadic tribe camps — and seasonal ger camps for tourists — can be set up or taken down in just one or two days.

Travelers visiting the Gobi Desert usually stay in ger camps. The comfort level of individual gers differs widely, often based on three factors: how far apart the operators locate individual units, what the location’s sanitary facilities are and whether any attention is given to basic cuisine.

We found a small new camp, the Gobi Mirage, to be comfortable and quiet, and its big ger-shaped dining hall was the source of fairly good meals. A more established camp, the Gobi Discovery, wasn’t as visitor friendly. Yet another, the Three Camel Lodge, was big and impersonal, but it had entertainment such as music and costumed dancers.

When we left the Gobi for a flight north to see the nearly extinct Przewalski horses (which have 66 pairs of chromosomes, differing from the standard equine 64) in Khustai National Park, we stayed at the Hustai Ger Camp, which was so insect-infested and unkempt that we left as early the next morning as we could.

Unfathomable vastness

Distances in the Gobi Desert are formidable. From the Gobi Mirage camp, one rides for about four hours and 140 kilometers, jouncing on barely visible washboard tracks, to reach the sand dunes. But it’s worth it.

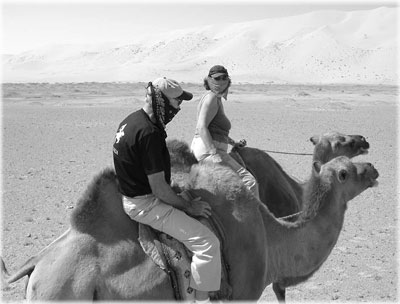

Astride easy-to-ride 2-hump Bactrian camels, happily not strung together with ropes, we actually struggled up into the loose sands. (I tried walking up when the camels couldn’t proceed any farther, but I had no luck, sinking thigh-deep into the soft sand.)

Except for the sand dunes, which rose several thousand feet into the solid blue sky at some spots, the entire area is pancake-flat. One can see across miles and miles of flat nothingness. Your driver had better know where the destination you’re headed for is or you might wander for days without encountering another vehicle.

Our other explorations in the Gobi were the Flaming Cliffs of Bayanzag, a worthy competitor to the Grand Canyon, and Eagle Valley, where we took another camel ride, this time as part of a connected string of Bactrians. A mini-stop let us pick up tiny fragments of dinosaur bones — at least, that was how they were represented. Our guide said the way to tell whether a minuscule chunk was bone or just a rock is to put it on your tongue. If it sticks, it’s bone. (We did and they stuck, so we brought some fragments back with us.)

After four full days in the Gobi, it was back on Aer Mongolia for our flight back to Ulan Bator.

Our Gobi Desert visit was arranged by Asia Transpacific Journeys (Boulder, CO; 800/642-2742, www.asiatranspacific.com). Including all internal flights, a final night at the Chinghiss Khaan Hotel and transportation to the airport for the flight home, the total cost was about $2,500 per person. If that seems expensive, consider the perils of showing up in the desert with no prearranged guides. Ugh!

Uniqueness squared

You may think that because you’ve visited the Sahara, you’ve seen the desert. ’Tain’t so. The Gobi sets a higher standard for vastness, nothingness and the kind of flat emptiness worthy of science fiction. Yes, you’ll be dusty and hot and maybe longing for a Big Mac, but you’ll have an experience you couldn’t match anywhere else in the world.