Paxos — Experiencing life fully on an idyllic Greek isle

by Harvey Hagman, Ft. Myers Beach, FL

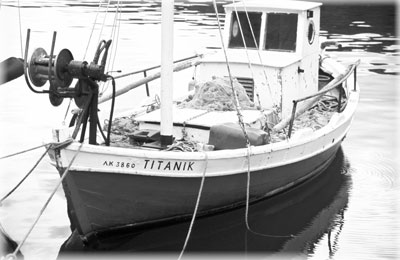

Little Paxos embodies what most people think of when they conjure up an image of an idyllic Greek island: brightly painted fishing boats; transparent, deep-blue water; small beaches in hidden coves; seaside tavernas; silvery olive groves; enchanting hiking paths, and little traffic.

On our 6-mile hydrofoil trip from Corfu, a Greek businessman told us, “There is something special about the sea and the sun and the light. Here you really feel like you are experiencing life fully.”

The Greeks call this small Ionian island, only 3 by 4½ miles, Paxi (pahx-ee); its anglicized name is Paxos. Although English hikers and European yachties love Paxos in summer, September is the best time for walking the island. We visited in September ’05.

A first look

The ferry deposited us at tiny Gaios, the island’s picturesque capital with caïques floating in its harbor and crumbling 19th-century whitewashed houses lining its shores. Locals pointed us toward the town’s bus stop — there was no sign — and soon the hotel taxi picked us up.

The Paxos Club Apartments Hotel is within walking distance of central Gaios. Our apartment’s rooms opened onto a balcony with looping white arches. Black wrought-iron railings cast shadows on the white tile.

After a tasty breakfast topped by a steaming cup of coffee, we picked up “The Bleasdale Walking Map of Paxos” and set off. A timeless stillness hung over this captivating island with dense, centuries-old olive groves, snaking stone walls, derelict farmhouses and abandoned stone olive presses. Here, there are more olive trees than people.

Exploring on foot

We caught a bus to Fontana, a village so small that we initially missed it. Most Paxos villages are little more than neighborhoods, many without central squares. Some have no shops or cafés, but most have churches. Many bear the names of the local families who founded them: Aronatika, Vassilatika, Tsenembesatika….

Our walk began at Fontana’s towering sycamore that looms over a silent square. The tree has become the village symbol and has given it its nickname, Platanos.

At a quiet kapheneia, local men sipped ouzo and thick Greek coffee.

“Kalimera!” we shouted. They returned our “Good morning!” as we began a hike along a stone path, once the principal route to the church of Estavromenos. Olive leaves shimmered in the breeze. Some of the treets in this grove are thought to be 500 years old, among the island’s oldest.

Centuries ago, the Venetians, in an effort to increase olive production, offered five drachmas (a considerable sum at the time) for every sapling planted. Soon olive trees sprouted everywhere.

Today the island produces Greece’s finest olive oil. To harvest the olives, Paxiots spread black plastic nets under the trees and swing away with bamboo poles.

Seaside vistas

We strolled to the 15th-century church with its engraved Byzantine emblem, the double eagle, on the stone bell tower. The church, restored in 1859, was locked, unfortunately.

We ambled on to intimate Longos, one of Paxos’ three ports. Venetians built most of the homes here 200 years ago.

Tavernas ring the breakwater. At our seaside table, I moved a chair to let a bus pass. At the next taverna, Greeks danced with English friends. Bouzouki music and laughter floated across the water as waiters raced to tables bringing more wine and food.

After a relaxing drink, we ambled on to the harbor’s far end and climbed a stony path to a crumbling windmill that overlooks the harbor. We paused to enjoy the panorama — to the left spread the rugged coast; below, the red-tile roofs of Longos circled the blue harbor.

We followed a stone wall along a ridge path to Dendiatika, a former pirate haven. As late as Venetian times, villagers lived high above the harbor for protection. Saint Charalambos, renowned for freeing Paxos of pestilence, has a church here.

Relaxing places

A rock-walled track took us to the bell tower of Agios Taxiarchos, the holy archangel. We proceeded through terraced olive groves to catch a bus back to the Paxos Club, where we sipped beers and munched snacks at the pool bar before changing into our swimsuits for a pleasant dip.

In the evening we dined at the high-ceilinged Paxos Club dining room, once a stony stable but now decorated with traditional farm and kitchen implements. We enjoyed a Greek salad, crusty bread, stuffed eggplant and succulent lamb with a chilled Macedonian white wine.

Freak hail pelted down during the night but disappeared quickly in the morning sun. Across the road was the sign for the stone-lined path to Ozias. Mists lingered as the path twisted and turned through the terraced olive trees.

The clouds lifted, and as we rounded a curve, Corfu’s vague outlines emerged. Soon the Pantokrator, Corfu’s great peak, slipped into clear view above the white sails of a passing boat.

We rested under the twisted, knurled, hollow trunks of olive trees, enjoying their mythical appearance. (Why does the mind turn philosophical in olive groves? Was that the Greeks’ secret?)

Then we snaked down a path to a remote beach where a boat bobbed at anchor. Nude swimmers frolicked, and we left them to their peace. Another ridgeline path led to a wider beach. It was ours alone, and we munched on a picnic lunch packed by the hotel, then plunged into the translucent waters.

Antipaxos

In the morning we picked up a caïque in Gaios and set off on the 30-minute run to Antipaxos, a tiny island 30 minutes away. Home to 120 Greeks, the island’s slopes are covered with grapevines. We docked at Agrapidia, strolled to Vrika Beach, enjoyed a simple lunch and sampled the forgettable but handy red and white island wines.

Later, we learned that the best and most popular beach was farther on at Voutoumi — a lovely stretch of golden sand.

The following day we joined our boatman on a ’round-the-island trip, cruising into dark grottoes and three mysterious sea caves under spectacular limestone cliffs. Dolphins, seabirds and turtles appeared. These caves are the Ionians’ most beautiful.

Back at the hotel, lassitude set in. We enjoyed the pool as the sun baked. At lunch we sipped retsina, the resinated wine that foreigners love to hate, and munched on spinach-and-cheese pies.

We decided to return on Aug. 15, 2006, to follow the faithful to the Monastery of Panagia (Moni Panagias) and join the festivities that last far into the night. Then we’ll continue exploring the island’s hiking paths.

Planning for Paxos

Paxos is a must for island hoppers and well worth the effort needed to get there.

Accommodations are difficult to find in July and August. Many tourists are return visitors, charmed by the friendly islanders, cozy feel and captivating scenery. One can cover the whole island by foot, though buses are regular.

During the summer, access to the island is easy by hydrofoil or excursion boat. By ferry, one can arrive from Igoumenitsa or Parga. (Only the former carries vehicles.) We took the hydrofoil from Corfu, which has an international airport. An excursion boat from Parga or Sivota is another option.

The Paxos Club Apartments Hotel (fax +302 662 032 097 [summer]; www.paxosclub.gr) includes 26 apartments, studios and suites. Apartments can accommodate up to five people, and each offers air-conditioning, TV, telephone, bathroom, kitchen, minibar, safe, radio and large veranda. Our apartment consisted of a bedroom, sitting room and kitchen.

There’s a large pool for adults, a small pool for children and a playground. It’s a wonderful place for families. Rates vary according to season, ranging from E99 ($120) for a studio apartment (two people) to E195 ($237) for a 2-room suite for four.

To obtain more information on Paxos, contact the Greek National Tourism Organization (645 Fifth Ave., Ste. 903, New York, NY 10022; phone 212/421-5777; www.gnto.gr) or visit www.paxos-greece.com.