Driving the Dalmatian coast, plus Croatia's Plitvice Lakes

By Jack C. Ogg, part 2 of 3 on the Balkans

The aqua-blue waters of the Adriatic, the coves and beaches of the Dalmatian coast, medieval walled cities, imperial Roman ruins, mountain lakes and the forests and vineyards of the interior make Croatia a modern-day Shangri-la.

A country of contrasts

Croatia is a relatively new country, and one of contrasts: geographic, political, religious and ethnic. Settled by the Illyrians, invaded by the Celts and, in succession, conquered by the Romans, Venetians, Byzantines, Ottomans, French and Habsburgs, it became a part of Yugoslavia after the First World War. After a devastating war with neighboring Serbia, peace and democracy came to Croatia in the 1990s.

Although it is predominantly Roman Catholic by religion and Croat by ethnicity, there are pockets of Orthodox and Muslim Serbs who now live in relative harmony in the new nation.

Croatia differs geographically between the northern lowlands, the mountains and 600 kilometers of coastline along the Adriatic Sea.

Zagreb

Our trip from Ljubljana to Zagreb, the capital, was a pleasant 100-mile drive through the rolling foothills of the southern Alps down to the plains surrounding Zagreb.

Zagreb is a contrast within itself, a microcosm of the nation. A city of about 800,000, it is a relatively modern metropolis yet Old World enough to have a “soul.”

The renowned Regent Esplanade Hotel, across from the train station that was built specially for the passengers of the original Orient Express, was, to our chagrin, undergoing a year-long restoration, so we stayed instead at the more modern Sheraton Zagreb (Kneza Borne 2). It is a beautiful, centrally located hotel with all the modern amenities.

Zagreb grew out of two medieval settlements, Kaptol and Gradec, and still possesses remnants of the towers and walled fortifications that protected and surrounded them. After the Ottoman onslaughts of the 14th century, the settlements expanded to the more modern Lower Town. While streets connect the two levels, a funicular is the most attractive way to traverse the two elevations.

Upper Town

Kaptol, in the Upper Town, is the ecclesiastical center of Zagreb, dominated by the Cathedral of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary (formerly St. Stephen’s). Originally Romanesque, it is now, after many transformations, Neo-Gothic in style. Its twin spires tower 105 meters over the city, and a beautiful fountain ornamented with a statue of the Virgin and four angels fronts the cathedral.

Farther up Kaptol Street are the curiae (the old residences of the cathedral canons), the Zagreb Tourist Board and the Dolac, the main city market, its square covered with colorful fruit and vegetable stalls.

We continued to the Stone Gate, once the eastern entrance to medieval Gradec, the other part of the Upper Town. It is now a shrine where people come to pray before a painting of the Virgin and Child. This painting was the only part of the old wooden gate not destroyed by an 18th-century fire.

Gradec is the administrative center and houses the Croatian State Parliament. True to its origins, craftsmen’s and tradesmen’s shops line the area’s streets alongside outdoor cafés. We visited its parish church of St. Mark, the interior of which contains Gothic and modern sculptures. The multicolored tiles on the roof display the coats of arms of Croatia and Zagreb. Nearby is an old mansion, now the Croatian Historical Museum, that is arguably the most attractive building in the Upper Town.

Next we saw the Lotrscak Tower, which may be climbed for a panoramic view of the city. Each day at noon, a cannon fires a round to commemorate a victory over the Turks. (The story is that a shot from the cannon landed squarely in the Turkish army commander’s lunch, convincing him to call off the siege of Zagreb.)

From the tower, a walk along the Strossmayer Promenade takes you to the funicular and thence to the Lower Town.

The Lower Town

A short walking tour of Zagreb’s Lower Town begins at the Ban Jelacic Square with its fountain of Mandusevac, where coins are thrown in for luck. It continues past the Stock Exchange, the spherical exhibition pavilion, the Flower Market and the Orthodox Church of the Holy Transfiguration.

Farther along, Marshal Tito Square is bordered by the National Theatre, the University Rectorate and the Faculty of Laws building and the Croatian School Museum. Zagreb’s two leading museums, Mimara and the Strossmayer Gallery of Old Masters, are easily reached and contain thousands of works of art, ranging from ancient Egyptian artifacts to paintings by Dutch, French and Spanish masters.

After touring the main railway station and passing the Botanical Gardens, we returned to our hotel for a short nap. We awoke hungry. The concierge recommended the Gallo Restaurant, and with good cause. It is situated at the end of a breezeway in a lovely outdoor courtyard. Although the service was somewhat

. . . leisurely, the food was excellent. We had salads, steak and risotto with a good local wine, plus an unusual but enjoyable side dish of spinach fried crisp in coconut oil. It cost $80 for two with wine and dessert.

The next morning, after our workout, we added the calories back with a full American breakfast served in the hotel’s beautiful dining room. While not a “steal,” our room and breakfasts, with discounts, came to around $200.

Republika Srpska and Bosnia

Departing Zagreb, we drove south into Republika Srpska, a part of Bosnia-Herzegovina established in 1995 by the Dayton Peace Agreement. The drive through Srpska revealed the problems and lack of facilities facing a developing region. The most obvious example was the lack of a commercial airport.

Srpska is heavily populated with Orthodox Serbs and was the political tradeoff to Serbia for the formation of Muslim-dominated Kosovo.

Leaving Srpska, we drove through an area of northern Bosnia that revealed its war-torn past. Entire villages were depopulated and contained only the shelled-out remains of houses and buildings. The drive back into Croatia was through a beautiful mountain-and-stream portion of northwestern Bosnia. We stopped at a picturesque restaurant overlooking a clear mountain stream with a series of rapids and dined on fresh mountain trout, local vegetables and cold beer for less than $20 total.

Plitvice Lakes

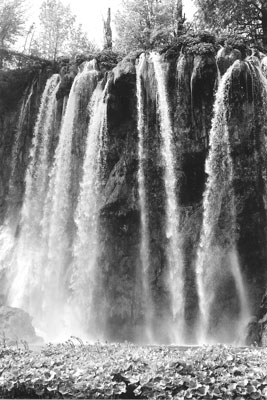

We crossed the Croatian border and proceeded to Plitvice Lakes National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Plitvice Lakes are actually a series of connected lakes originating in the Bijela and Crna rivers — the White and Black rivers — and additionally fed by many underground springs. The system of lakes is connected by a succession of waterfalls and cascades, beginning with Lake Proscansko at the top and linked one below the other.

We rode the park bus to the top and commenced our walk over a series of wooden bridges and down footpaths that wind leisurely above, around and below each lake. The falls and cascades tumble and foam their way to each lake below with wild abandon.

The lakes are separated by barriers of limestone and encrusted plants that form a series of natural travertine dams that create the cascading falls. We are not avid trekkers; still, the walk down was easy and took only about 2½ hours. We were told that there really isn’t a bad time to visit.

Inside the park there are three hotels, all clustered near Lake Kozjak. Hotel Plitvice is the newest and best of the three. Unfortunately, it was full, so we stayed at its sister facility, Hotel Bellevue, at $75. While it was more spartan, drinks on the balcony of the Plitvice and dinner at its restaurant with the magnificent views soothed our feelings. Next time, we’ll make reservations ahead.

On to Zadar

We left Plitvice Lakes and followed the mountainous road to Zadar, stopping only at noon at a small mom-and-pop restaurant for an unbelievable pig sandwich and cold beer. Many of the restaurants of the upper Balkans have huge open spits that continually roast pigs, goats and sheep. You can drive along and pick out your restaurant, where they carve your order from the open grill. The drive to the coast also offered some stunning views of the shimmering Adriatic.

The Old Town of Zadar occupies a peninsula bordered by a channel and harbor encircled by high walls. The streets within the walls are paved with gleaming white stones and teem with people strolling, shopping and conversing at the outdoor cafés.

We visited the beautiful Church of St. Donat, a circular edifice of early Byzantine architecture built over an ancient Roman forum. Although it was near midnight, the choir was still practicing, and Connie and I sat mesmerized through three or four choruses. We didn’t understand a word, nor was it necessary to do so.

Although we had dined earlier, at the Restaurant Albin, we enjoyed late-night coffee and pastries with the locals before heading to our hotel, several miles from the Old Town. There are three or four hotels in the Borik Hotel Complex that all operate with the same management. They range from “essential accommodations” to beach-touristy. Ours, the Novi Park Hotel (Majstora Radovana 7), was in the middle, at approximately $70.

The journey to Split

We left the next morning for Split, stopping for pastries in Vodice, a neat coastal town. In fact, the entire coast is dotted with little towns, B&Bs, resorts and apartments. Although we stayed mostly in the larger towns, accommodations on the coast would not be a problem, except possibly during the summer when the Western Europeans descend.

We continued on through Sibenik, then journeyed to the medieval town of Primosten, which sits on a small peninsula. We enjoyed a great open-air lunch and visited with two European gentlemen, a Dane and a Slovak, who were with the European Union peacekeeping mission. They told us some interesting stories about the wars and history of the Balkans.

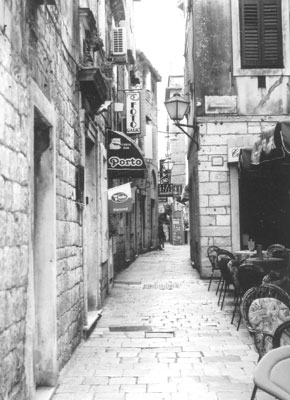

Our next stop was Trogir, another walled city of narrow pedestrian streets and medieval alleyways fronted by a wide promenade. In the center of the maze is the giant Cathedral of St. Lovro, which was under restoration. We lingered over espressos before finally driving the short distance to Split.

The city of Split is the crown jewel of the central Dalmatian coast. It sits on a high peninsula fronting several of the many islands of the Adriatic.

To get to the Old Town, you must pass the highrises and military port of a modern industrial city. Fortunately, the Old Town still exists. It surrounds Diocletian’s Palace, which faces the harbor and not only contains some of the finest remaining Roman ruins but also has over 200 houses, shops and cafés within the palace’s boundaries.

We spent our evening visiting with Justine “Cici” Tomaseo, a friend of a friend. She lives in Old Town in the building she was born in, despite her many years as the wife of an Egyptian prince in Cairo. Cici paints beautiful icons, is a spry 80 years young and lives with her 101-year-old aunt who still gives piano lessons.

After dinner, we returned to the Hotel Globo, Old Town’s newest hotel, an excellent 4-star establishment with a 2-star price tag ($175-$200).

Diocletian’s Palace

The next day, we began our tour of the palace boundaries at everyone’s recommended place of beginning, the imposing black statue of Gregorius of Nin. Sculpted by Ivan Mestrovic, Gregorius’ left toe is polished clean from people touching it for its supposed good fortune.

We entered through the Golden Gate (North Entrance) and saw the Papalic Palace, once the home of a wealthy nobleman. The interior houses the Municipal Museum, which contains furniture, old coins, drawings and heraldic coats of arms from the 17th century.

Continuing on the narrow street, we stepped down into the Peristil, which was the ceremonial entrance to the Imperial family apartments. The Peristil, though lined with columns and stone friezes, now has an outdoor café in its center where people gather for coffee, food and pastries.

To the east, the stairs lead up to the magnificent Cathedral of St. Domnius. The carved wooden doors portray 28 scenes from the life of Christ. The cathedral is octagonal and encircled by columns, with an overhead frieze of Diocletian and his wife in its domed interior.

Originally built as that emperor’s mausoleum, it is ironic that it became a cathedral. Diocletian despised Christianity, and, despite his wife’s and daughter’s being Christians, he was responsible for the suffering and martyrdom of many Christians. His body was placed in a sarcophagus in the center of the cathedral after his death in A.D. 316.

A bell tower soars 200 feet and provides a great panoramic view of the Old Town and its environs. From the Peristil, you can visit the vestibule and Diocletian’s apartments that fronted the sea. The floor below, the Podrumi, is a maze of chambers, and the main passage is lined with touristy stalls selling jewelry, ceramics and souvenirs. It opens to the southern façade facing the sea, where boats could enter directly in Diocletian’s time.

We strolled the streets and shops of the palace area, visiting the other entrances and gates (Brass, Silver and Iron).

We decided to have dinner at Restaurant Sumica. It is located on the sea, amid pines and cypresses, with dinner served on an open-air terrace. The breathtaking sunset was matched only by the food, which was a bit pricey by Croatian standards ($48 for two).

Our dinner began with an unusual pâté followed by fresh fish, scampi, fries and a good local white wine. The fish, called orada, is the favorite fish of the Dalmatian coast; the scampi were large and succulent. Oh, but what a romantic ending to a gorgeous day

Next month, the journey along the Dalmatian coast continues.