France — following the footsteps of a soldier

by Kaye Olson, DeWitt, MI

After traveling to 41 countries, my husband and I embarked on a self-designed journey that would surpass all the trips we had taken in our lifetime. Over several years we had searched for information regarding the death of my uncle, Staff Sergeant Lewis (Louie) Annear, during the WWII Normandy invasion of 1944. Our mission was firm. After a time lapse of 57 years, we would follow Louie’s footsteps from his D-Day disembarkment on Utah Beach till his death near St-Lô on July 11, 1944.

Louie completed the African and Sicilian campaigns, then trained as a Raider in southern England to prepare for the Normandy invasion. In WWII he served in the 47th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division. From my relatives, we accumulated Louie’s letters, governmental replies and pictures. Although I was only four years old in 1944, I remember my family discussing his activities. In letters to my mother, he often mentioned me. However, because of security, his letters from England and France could not list locations. We needed more information.

Preparing for the journey

Following a Web search, we found only one book solely dedicated to the 47th Infantry, which was invaluable in finalizing our journey. We purchased books and maps to take along. One book that guided us daily was titled “Battle of Normandy — Official Guide,” published by Gallimard Guides and available online from www.thebookplace.com and www.whsmith.co.uk. Its historical accuracy, pictures, diagrams, maps and practical information impressed us.

For research, we purchased several books from the Historical Division of the U.S. War Department (http://bookstore.gpo.gov). Available at bookstores, the “Michelin Green Tourist Guide: Normandy” and Michelin’s map No. 231 (specific to Normandy) proved essential.

As on previous trips, we involved Carol, our travel agent. She secured flights, car rental, hotel reservations and cancellation insurance. From AAA, we obtained the optional International Driving Permit. Now, we were set.

Utah Beach

On May 10, 2001, we flew from Detroit Metro to Paris’ Charles de Gaulle International Airport for two weeks in France. After luggage retrieval, we cleared Customs, then found Kemwel Auto Rental (phone 877/820-0668 or visit www.kemwel.com), where we picked up our new, bright red Citroën with a stick shift. With maps in hand, we headed to Rouen, less than two hours away, to acclimate ourselves to the time change and prepare for our journey.

The next morning we headed for Utah Beach, where Louie had disembarked in early June 1944. As we surveyed the flat beach in silence and watched the gentle waves roll in, it was impossible to visualize the invasion 57 years earlier — the blood, the bodies in the water — although we knew Utah Beach had never been like “bloody Omaha.” Gazing inland, we noted a “bunker-like” museum in addition to the homes that now graced the beach. After exploring the Utah Beach Landing Museum and WWII monuments, we moved on.

A short distance away, we arrived in Ste-Marie-du-Mont, the first village on the main road from Utah Beach. The old church was beautiful, its nave dating to the 12th century. We strolled the village, viewing the brick homes, shops and WWII commemorative monument.

In the countryside, the roads were narrow with many curves, but they were well marked. Crucifixes and shrines frequently adorned crossroads. We entered bocage country: the woodland and hedgerow areas of France. For miles, solid shields of hedgerows eight to 12 feet high and six to eight feet deep hid the farms and dairy cows from the road. It was understandable how American infantrymen were surprised by the German panzers and soldiers hiding behind these leafy hedges. Casualties were so high here that the battles in these areas were collectively called “War of the Hedgerows.”

Sebeville & the Merderet River

Sebeville was next, just a crossroad with several old homes where Louie and the 47th had spent their first night. During the war, many landings occurred in the area, with gliders crashing into trees and farmhouses. The terrain was quite flat.

On June 14, 1944, the 47th Infantry crossed the Merderet River, mentioned in the movie “Saving Private Ryan.” During the war, this area was marshy and flooded by the Germans, causing serious problems for Allied soldiers and paratroopers. As we arrived at the river, the setting was tranquil. We walked around and studied the beautiful monument to our paratroopers, the American flag flying high.

Along our route, meals were economical and easily available. For lunch, we would purchase a freshly baked quiche ($1.25-$3 each) from a patisserie, a sandwich from a bakery or soup from local sidewalk cafés. We never paid more than $10 for the two of us. Dinners cost $12 to $15 for each of us.

Even in Paris in the Sacré Cœur area, local restaurants offered competitive dinner specials for $15 or less per person.

The advancing front

Continuing our journey, we arrived at Orglandes, where several of the infantry battalions had met with stiff German resistance. On June 17, Orglandes was liberated.

We found this village quaint, with an impressive old church. Surrounding this church was an old stone wall that displayed a WWII 50th anniversary commemorative plaque with a tub of beautiful flowers below.

The 47th Infantry completed several missions after crossing the Douve River at St-Saveur-le-Vicomte. Moving west, the First, Second and Third Battalions of the 47th engaged in different activities to achieve the main objective of sealing off the Cherbourg Peninsula. Their advancement was so quick, they caught the Germans off guard. Louie’s 9th Division was recognized for the greatest advance of the invasion since D-Day.

After exploring the beautiful city of St-Saveur-le-Vicomte, we drove to Bricquebec, then on to Equeurdreville. On June 20, a fierce battle ensued within Bricquebec. The Germans had reinforced themselves with heavy artillery, machine guns and mortars and American casualties soared. Even though Allied bombing pounded ahead of Louie’s Raiders on June 22, they took a beating, as did the Equeurdreville area, which was the last heavily defended city prior to Cherbourg.

Continuing to St-Lô

Driving to Cherbourg, the flat marshes and hedgerow areas gave way to a drier terrain with some hills. Viewing the port, we grasped what a strategic position it was during the war. As the 47th Infantry entered Cherbourg on June 25, they found it completely devastated. By June 27 the city was liberated and several divisions, including Louie’s 9th Division, held a celebration at the Napoleon statue on the square.

On a day trip, we drove to Cap de la Hague, where the 47th had gone to stop German resistance. Even with 3,000 Germans in highly fortified areas, the Raiders prevailed, ending the resistance on the peninsula.

Driving south toward St-Lô and back into hedgerow country, we stopped at St-Jean-de-Daye, a pleasant village ablaze with flowers. The war monument dedicated to the children of the village touched us. It was here that the soldiers overwhelmed the Germans on July 7th near the canal on the north side.

St-Lô and surrounding area

Using St-Lô as a base for three nights, we set out to find La Caplainerie, where Louie was killed in action. After driving 45 minutes without success, we stopped at a French farm. The woman couldn’t speak English and we spoke minimal French, but with the map and our gesturing, she finally understood. With a smile, she pointed ahead. We were one crossroad from the area.

Arriving at La Caplainerie, we followed in Louie’s footsteps down a narrow road smothered by hedgerows. It was an emotional experience; to have shared the path on which he died proved overwhelming. The area was strangely quiet with no activity, simply a few farms and houses. On July 11, while leading his squad on an enemy attack, Louie was killed here instantly by shell fragments from a ruthless German panzer attack on his division.

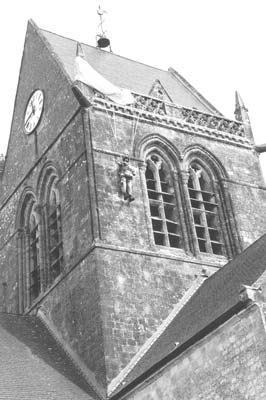

We then drove to Ste-Mère-Eglise, a lovely village with WWII significance, where Louie was buried. Prior to the land invasion, paratroopers from the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions dropped into this area. One paratrooper, Private John Steele, got his parachute caught on the church steeple, an event referred to in the movie “The Longest Day.” One story tells that he faked death for two hours, surrounded by Germans, till he was cut down. Glancing up at the church, we spotted the likeness of John Steele suspended in a parachute harness on the steeple.

Entering this 11th- to 13th-century church of Norman and Gothic architecture, we noted a WWII commemorative stained-glass window. While I stood still taking in the quaint interior, an overwhelming force of energy whipped around my legs three times, immobilizing me for a few seconds. Immediately I turned to my husband and said, “Louie was here.” I felt Louie’s presence; he commanded my attention. It was a remarkable event.

The end of the journey

On the village square, the Information Center staff directed us to the former Military No. 2 Cemetery after viewing the photo we had taken with us.

In 1944, the Ste-Mère-Eglise Cemetery was the first WWII American cemetery in France, with 5,000 soldiers laid to rest there. But in 1948, all remains were exhumed and either sent home or transferred to the French cemetery at St-Laurent-sur-Mer. (Louie rests in St. Mary’s Cemetery, Richland Center, Wisconsin.)

At the entrance to the cemetery, a monument pays tribute to Louie’s 9th Infantry Division. We stood at the cemetery site, now a sports field with purple and yellow weeds blowing in the breeze. The scene was one of complete tranquility.

To bring closure to Louie’s journey, a visit to one final area remained: the American Cemetery above Omaha Beach, which every traveler to the area must visit. We walked among the gardens, reflecting pool and chapel, then admired the 22-foot-tall bronze statue in the memorial structure called “The Spirit of American Youth Rising from the Waves.” We gazed over the 9,387 white crosses of the servicemen and women buried there, including 307 unknowns, with a sense of reverence and sadness.

At the visitors’ building, cemetery Superintendent Gene Fellinger verified data on Louie and copied cemetery photos from a book published after the war. Then he asked us to step outside. From the depths of Omaha Beach, his staff played “Taps,” honoring Louie, while he presented me with small, weathered French and American flags and tears rolled down my cheeks.

Noteworthy sites

Having completed tracing Louie’s journey, we set our sights on our other objectives. Along with visiting the four other beaches which played a role in WWII (Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword), we covered most of the war museums in the area; we found the Museum for Peace in Caen exceptional. “Normandie Terre-Liberté” signposts guided us along the Battle of Normandy route.

After this emotional week, we moved onward to lighter times. During our second week, we visited Mont-St-Michel, then headed into the Loire Valley to explore our six chosen châteaux: d’Azay-le-Rideau; Villandry (with some of the most beautiful gardens in France); Chenonceaux (on the Cher River); Chambord (the largest château in the Loire Valley); Amboise, and Chaumont.

Ending our tour in Paris, where we spent three days, offered a respite before flying home.

Looking back

Following Louie’s footsteps was an unforgettable journey. In retrospect, would we have done anything differently? Probably not. By traveling in May, we avoided the peak season. Perhaps the trip went so well because of our meticulous planning or because we are well-seasoned travelers.

For a total of $3,145, including flights ($1,332), car rental ($412), International Driving Permit ($36), gas ($161), lodging with breakfast ($760) and lunches and dinners ($444), the two of us experienced the trip of a lifetime.

Did anything go wrong? Returning our rental car to the airport, we found poorly marked signs for our drop-off point — insignificant.

I’ll never fully understand all of the powerful emotions attached to this journey, all for a lone soldier from WWII whom I never really knew. How could I care so much about events that happened so long ago? Was the trip so meaningful because I made the journey for family or because I knew I would never return?

Within each person, there is a trip that must be taken, whether driven by a dream or driven by family. Don’t wait. Plan it now.