Laos — land of a million elephants

by Richard Shally, Walnut Creek, CA. Photos by Henk Ten Dam, Netherlands

Laos is known as “the land of a million elephants,” but are there really a million? To find out, I took a 17-day Small Group Discovery Tour with Carpe Diem Travel, a UK-based socially responsible tour company. The January ’07 tour started and ended in Bangkok.

After our arrival, an introductory meeting was held by our tour leader, Marc Lansu, for the 12 world travelers who were about to begin this memorable journey to Laos, one of the least-visited and poorest of the Southeast Asian countries.

Starting out

We took the overnight train from Bangkok to Ubon Ratchathani, where we boarded a minivan for the 2-hour drive to the Lao border. At Chong Mek we exited our van and walked across the border to the Lao Immigration office, where they required $35 and a passport photo for a visa. The officials took our money and our passports, then we were ushered around the corner to another window where we were asked for another $10 to cover Customs costs and retrieve our passports.

In some foreign lands, the new color overprinting on U.S. currency has caused confusion. However, the Lao border guards accepted only the new U.S. currency which displays the color overprinting.

We boarded another minivan and drove about an hour from the Thai border to Pakse, Laos, the provincial capital of Champasak Province, crossing the Mekong River for the first time. After lunch in Pakse ($3 for a very filling combination of Thai and Chinese cuisine with a mixture of Lao spices thrown in), we headed south toward the “4,000 islands” region on the Mekong.

On the way, we visited the amazing Wat Phou temple built by Khmer stonemasons during the sixth to eighth centuries. Today, Wat Phou is a UNESCO World Heritage Site undergoing major excavation, started in 1996.

Life along the Mekong

Laos, at just over 90,000 square miles, is roughly the size of Great Britain or the state of Utah. With a population of just over 6.5 million, it is one of the most sparsely populated countries in Asia. The majority of the people live along or near the Mekong River, which flows from China in the north and along the border with Thailand to the west and on to Cambodia and Viet Nam to the south.

Laos has no railway system plus very limited paved highways and limited commercial airline flights between towns, so the Mekong provides not only sustenance but about the only means of transportation for many people in this landlocked country.

We crossed the river on a ferry on our way to our first night’s accommodation on Don Khong just in time to witness a spectacular sunset over the Mekong. We stayed two nights in a beautiful villa on the banks of the river.

I got up early the next morning to watch the sun rise over the Mekong and, as I was waiting for that magical moment, I noticed a group of monks coming down the road with their bowls to collect their daily alms. As I peered across the river at the sunrise, the monks made a semicircle behind me and chanted as the sun came up over the horizon. Though I did not understand their chanting, it was one of those memorable and spiritual moments that I shall never forget.

That day our group boarded a longboat for the 2-hour journey down the river to see the Li Phi waterfall. This cataract, plus the larger Khone Phapheng Falls on the east side of the river, is what prevented the French from using the Mekong to travel north to open the internal China market in the late 1800s.

Since we were visiting in the dry season, the river level was low, allowing us to see how the native villagers along the banks used the flood plain to plant gardens. We also saw people fishing and bathing and cattle and water buffalo drinking along what is known as the “mother of all rivers.”

Lao geography

Over 70% of Laos is covered with mountains and forested hills, so the river plains that can be cultivated are essential to the country’s food production. The only other level land, apart from the flood plains, is on the mountain plateaus.

The largest, the Xieng Khouang Plateau, is located in the north and is home to the famous Plain of Jars.

We would visit that area later in our journey, but we were now headed to Bolaven Plateau, the more fertile of the two major plateau areas in the country. With a cooler altitude at 1,000 meters and with plentiful rain, the area is suitable for temperate crops like rice, coffee, tea, cotton, durian, peanuts and cardamom.

The minority Laven tribe, for whom the plateau was named, is famous for their handwoven cloth, which they sell alongside the highways in the area.

On our drive to the plateau, we had our first encounter with Lao elephants. Two elephants with riders scrambled up onto the highway just ahead of our van. They were being used to deliver goods to villages located in the local mountains.

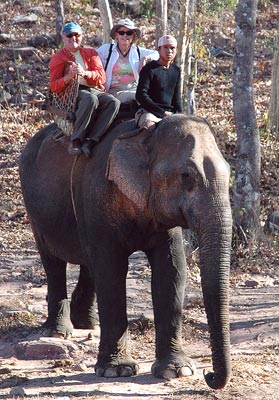

The next accommodations for our group were in stilted cabins nestled deep in the forest next to the Tad Lo waterfall. It was here that my wife, Pat, and I had our second encounter with an elephant, as we signed up for a 2-hour jungle safari for the grand price of 50,000 kips ($5).

It was a rather leisurely trek, as our elephant stopped constantly to graze on the surrounding foliage. I was amazed at just how agile and surefooted the animal was in crossing streams and moving up the banks.

From Champasak Province in the south, we headed over 700 kilometers north along the Mekong to Viangchan Province and the capital of Laos, Vientiane. The main north-south route is highway 13, a 2-lane road with very little traffic. The highway is in good condition, but there are no shoulders, so when a vehicle breaks down or has a problem it just sits, blocking its lane.

Money matters

We found that the U.S. dollar, the Thai baht and the Lao kip could be used interchangeably for purchases, but the change given was most often in kips.

Vientiane was the only town in Laos where we found ATMs. The local bank limited the withdrawal amount to 700,000 kips ($70). The money was dispensed in 10,000-kip notes, so I left the machine with a sizable roll of the local currency.

The money went a long way, though, as a typical lunch would cost between 30,000 and 50,000 kips ($3-$5) and dinners would be 60,000-90,000.

In Vientiane, a dinner at a traditional Lao outdoor restaurant consisting of a rice noodle soup called foe cost 40,000 kips, and that included a bottle of the local brew, Beerlao.

Community involvement

As part of Carpe Diem Travel’s philosophy of social responsibility, our group had lunch at a Vientiane restaurant, Peuan Mit (Close Friends), operated by a non-governmental organization (NGO) that supports street children. That afternoon we visited the facility run by the same organization, Friends International, which provides a social service program offering food, education and a sense of community to young children in need.

We toured the capital city via a motorized tuk-tuk accompanied by our local Lao guide, Mr. Air Phovanh (just Air, to us). His English was very good, and he explained the significance of the most important national monument in Laos, Pha That Luang, or the Great Golden Stupa. We also viewed the Patuxai, Vientiane’s 4-arched answer to the Arc de Triomphe.

During our three days in Vientiane, we visited several other renowned temples, strolled along the banks of the Mekong River and shopped at the Morning Market, the largest of its kind in Laos.

Our next stop heading north from Vientiane was the town of Vang Vieng on the Nam Song River. The area is famous for its striking limestone karst geology and its many caves. We stopped for lunch at the Organic Farm, founded in 1996 to introduce organic farming to an area where chemicals and deforestation were destroying the land. Profits from the farm are used to support and educate the local community. The farm promotes the use of natural materials and traditional methods to produce silk, wine and mulberry tea.

My lunch at the farm consisted of a plate of crispy fried mulberry leaves (10,000 kips), a mulberry fruit shake (8,000 kips) and a bowl of vegetable soup with chicken (15,000 kips) — a very unusual and satisfying meal for $3.30.

Xieng Khouang Plateau

Then it was on to the Xieng Khouang (Xiang Khoang) Plateau. The road to the plateau was newly paved but only two very narrow lanes, and it wound and twisted through miles of beautiful high, green mountain scenery. There are many villages along the highway, and their activities spill out onto the road as it’s the only level place to conduct business and for children to play.

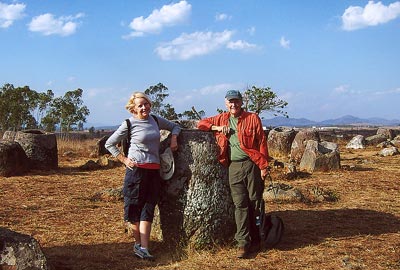

The mysterious Plain of Jars awaited, rewarding the visitors willing to undergo the arduous trip up to the plateau. Situated near the town of Phonsavan, several groups of enormous stone vessels (some weighing over 10 tons) are scattered about the landscape. How they got there, what they were used for and how they have survived the fighting that ravaged this area during the Second Indochina War remain mysteries.

Laos is reputedly the most heavily bombed country in the history of warfare. Bomb craters dot the landscape, and unexploded ordnance is still a major problem in this area of the country. We were warned to stay strictly within the white markers, denoting safe paths, while we headed off to view the jars up close.

A major NGO working in this area is the Laos National Unexploded Ordnance Programme, or UXO Lao for short. Their mission is to find and destroy bombs, mines, grenades and various leftover explosive devices to make more of the country safe from detonation of these hazards.

We visited the local UXO operation in Phonsavan and had a chance to see firsthand the daunting task they face in finding and disabling these myriad ancient weapons.

An international survey found that 25% of all villages in the country are socioeconomically affected by unexploded ordnance. At the current rate of removal and destruction, the UXO group feels that it could take 50 to 60 years to clear the country of all unexploded ordnance. This was a very sobering part of our visit to Laos.

Luang Prabang

At the junction of the Mekong and Khan rivers, Luang Prabang was the traditional royal capital of Laos. Today, the town is home to more than 30 wats (Buddhist temples) plus some of the best examples of French colonial buildings in Indochina.

Some of the key places to visit are the Royal Palace Museum and Mt. Phousi, in the center of town, to view the sunset over the Mekong River.

An event not to be missed is the vibrant night market that stretches the length of Sisavangvong Road. Local vendors display a huge array of woven silks, clothing, jewelry and local crafts under strings of twinkling lights.

The highlight of our visit to Luang Prabang was our boat ride up the Mekong River to the Pak Ou Caves. Our guide on this excursion was Mr. Daoluck Bounsavath, or Lucky to our group. The caves are about 15 miles upstream and house more than 4,000 Buddha statues, placed there by worshipers.

On our way back from the caves, we stopped at several villages where the locals make a living weaving silk, brewing potent rice whisky or making paper from mulberry tree bark.

A very special stop on this tour was at Lucky’s village, which consisted of 14 woven paneled houses with grass roofs. There is no electricity, no running water and no land access to the village. The people of the village, like so many of the Laotians we met, were welcoming, happy, gentle, beautiful souls — especially the children. With just a simple “Sabai di” (“Hello”) or “Khawp jai” (“Thank you”) from us, their faces lit up in recognition.

Summing up

We got up at 5:30 on our last day in Laos to witness, along the main street of Luang Prabang, the ritual of the offering of alms to the local monks.

It was a very moving experience watching the several-block-long procession of monks silently flowing by in saffron robes. Kneeling locals and a few tourists placed balled-up mounds of rice in the alms bowls for the monks to eat later at the monastery.

Did I see a million elephants on our tour? No. But I now have a much better understanding of the importance of the elephant to the Lao people. I came away with an appreciation of the Buddhist belief that the elephant is not only a symbol of greatness and wisdom but a vehicle for transport and work.

This 17-day small-group tour, which operates year-round, cost £1,095 ($2,274) per person, land only, based on double occupancy. For more information, contact Carpe Diem Travel (London; phone +44 [0] 845 226 2198, www.carpe-diem-travel.com).